The Trouble with Forecasting House Prices

Complex and complicated, but the outlook is poor

September 2023. Reading Time: 10 Minutes. Author: Nicolas Rabener.

SUMMARY

- House price growth is based on supply & demand imbalances or speculation

- Residential property prices can be flat or declining for decades in real terms

- The long-term outlook for house prices is poor for most countries

INTRODUCTION

Mortgage rates have doubled and tripled in some countries since 2021. So why aren’t residential real estate markets more distressed?

For example, the average home price-to-income ratio in the United Kingdom is at an astounding 9x. This implies that most borrowers are spending more of their income on interest and amortization payments than ever before. The typical UK mortgage is five years, but the interest rate for a new loan has increased from 1.8% a year ago to 4.6% today. Many borrowers will not be able to refinance at this level and will be forced to default. The bank will then sell the home, putting more downward pressure on the housing market.

Yet property markets continue to surprise. Many, including this author, thought that UK homes were already overpriced at an average home price-to-income ratio of 6x over the last decade. Then these homes became even more expensive. Perhaps governments will step in and support borrowers as the political pressure rises. Or maybe inflation will cool, and central banks will lower interest rates.

Since many variables influence housing prices, assessing residential real estate as an asset class is a complicated endeavor. So what are the key drivers of the sector, what are some of the common misperceptions, and what is the long-term outlook?

SUPPLY & DEMAND

Residential real estate prices are influenced by either fundamental supply and demand imbalances or simple speculation. The former is easy to understand: When demand outstrips supply, prices tend to appreciate. Supply could be constrained by natural population growth, immigration, urbanization, regulation, or some combination thereof. The trends tend to differ from countryside to city and even within cities, which makes it difficult to gain a clear picture of the true state of the housing markets.

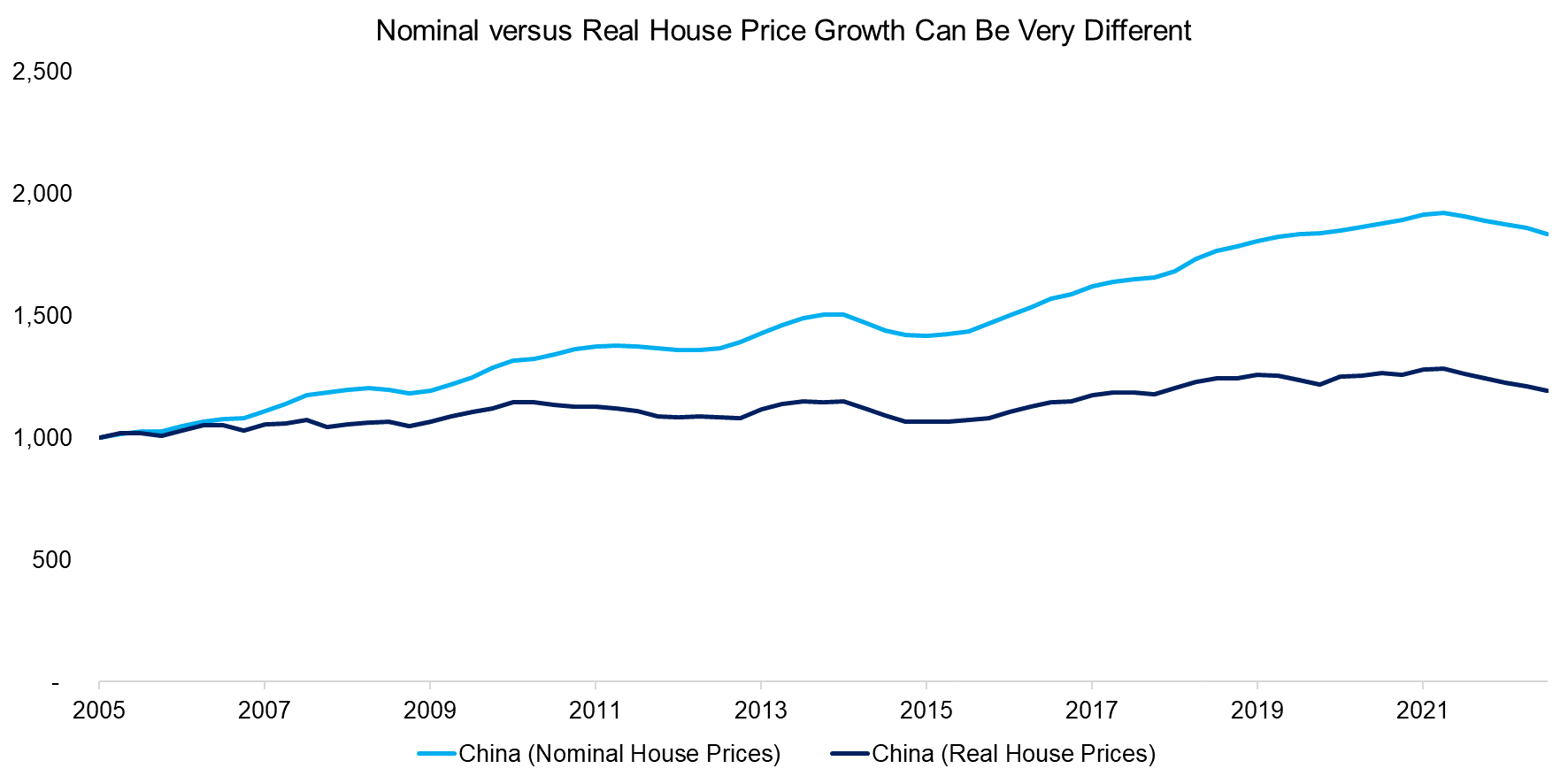

Differentiating between nominal and real post-inflation returns is critical when evaluating real estate investments. For example, residential real estate in China looks like it would have been a sure bet over the last two decades given the country’s phenomenal economic growth. But while that may be true for Shanghai and other cities, Chinese home prices only rose at a nominal rate of 3.5% per annum between 2005 and 2022. That compares to an annual GDP growth rate of 8%. So in real terms, residential real estate may not have been so great an investment as China’s economy overall.

Source: BIS, Finominal

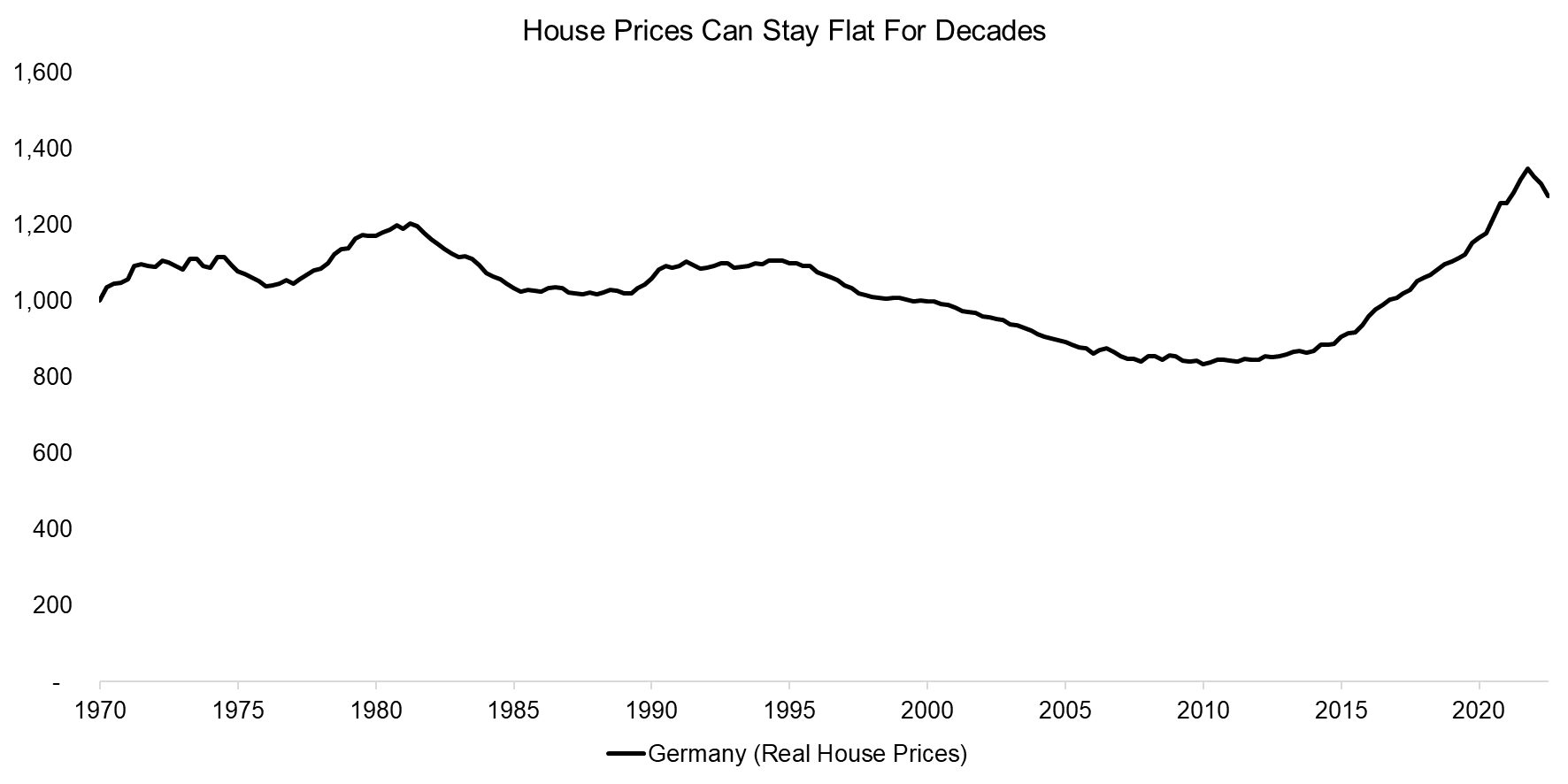

That residential real estate will appreciate over time is a common assumption, but it is not always the case. When a housing market’s supply and demand balance is in equilibrium, prices can remain stable for decades. For example, Germany’s population rose only slightly from 78 million in 1970 to 83 million in 2022, and real house prices hardly budged over the entire period.

Source: BIS, Finominal

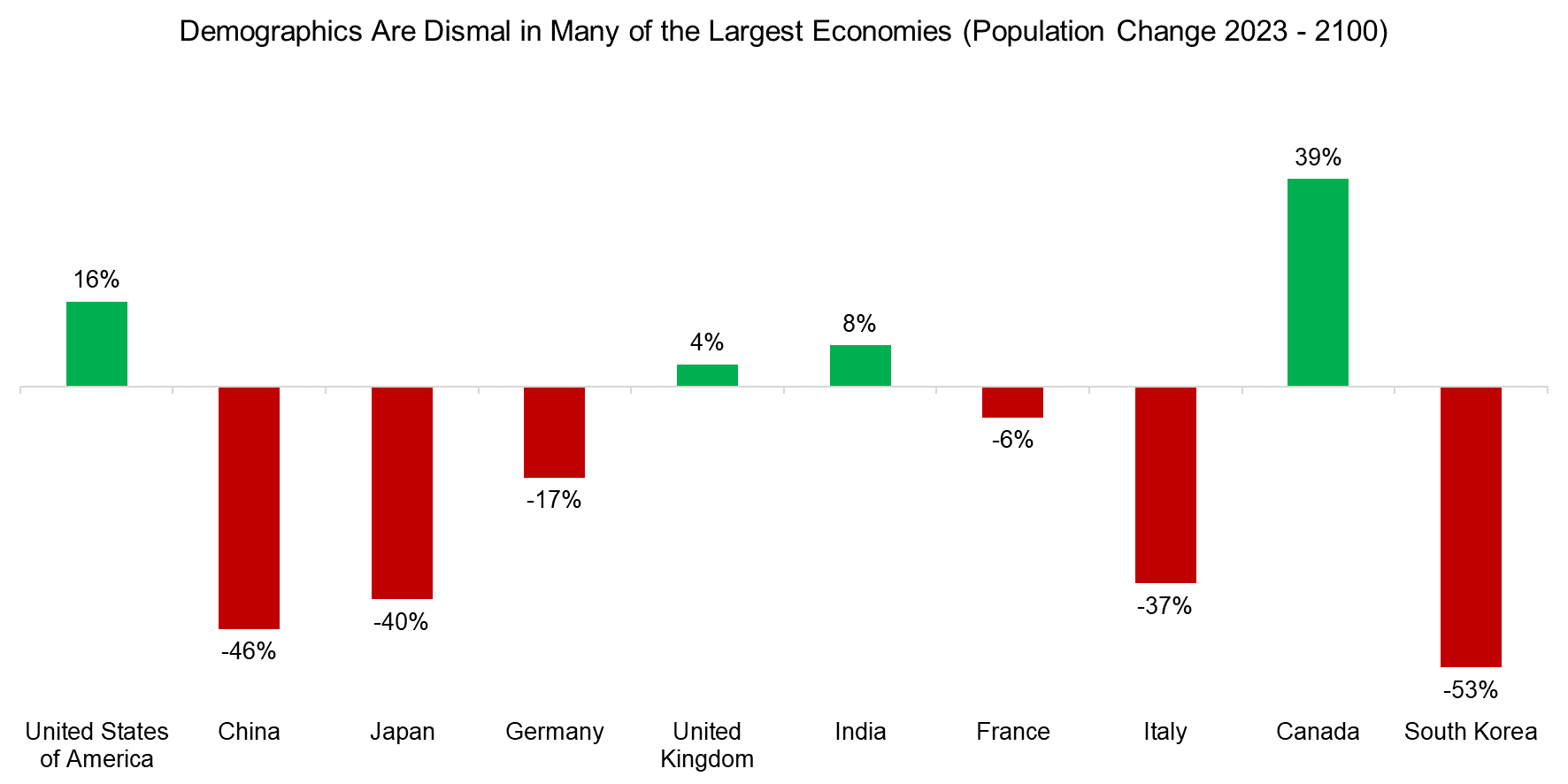

Based on fundamental demand, the long-term outlook for residential real estate in the world’s 10 largest economies looks pretty dismal. With only four of these nations expected to grow in population over the next 80 years, all 10 are expected to shrink by a cumulative 600 million people or so (read Aging & Equities: Selling Stocks for the Long-Term).

Efforts to increase fertility rates by offering more childcare benefits or otherwise incentivizing population growth have largely failed. Increased immigration may help, but few countries have experience with the sort of large-scale immigration that will be required and even those that do can often face internal resistance.

Most of the decline is expected after 2050, but Japan will shrink by around 25 million people between now and then, according to United Nations estimates, and is already feeling the effects. Many rural areas have experienced rapid depopulation, and local municipalities have a hard time funding and staffing schools, hospitals, and other public infrastructure. Some towns now offer tax breaks to newcomers or just pay people outright to relocate there. Either way, there is less demand for housing, and that will ultimately mean lower prices.

Source: UN, Finominal

SPECULATION

Speculation is another key driver of housing prices and comes in many varieties. Sometimes prices rise due to a supply and demand imbalance. This persuades investors to pour their money in and creates a positive feedback loop.

In some countries, entire generations have been raised on the concept of the property ladder. In the UK, that has meant buying a small flat after university, selling that once it has appreciated in value, buying something slightly bigger, and hopefully laddering up over the years to a large house in the countryside. Naturally, this assumes home prices appreciate forever.

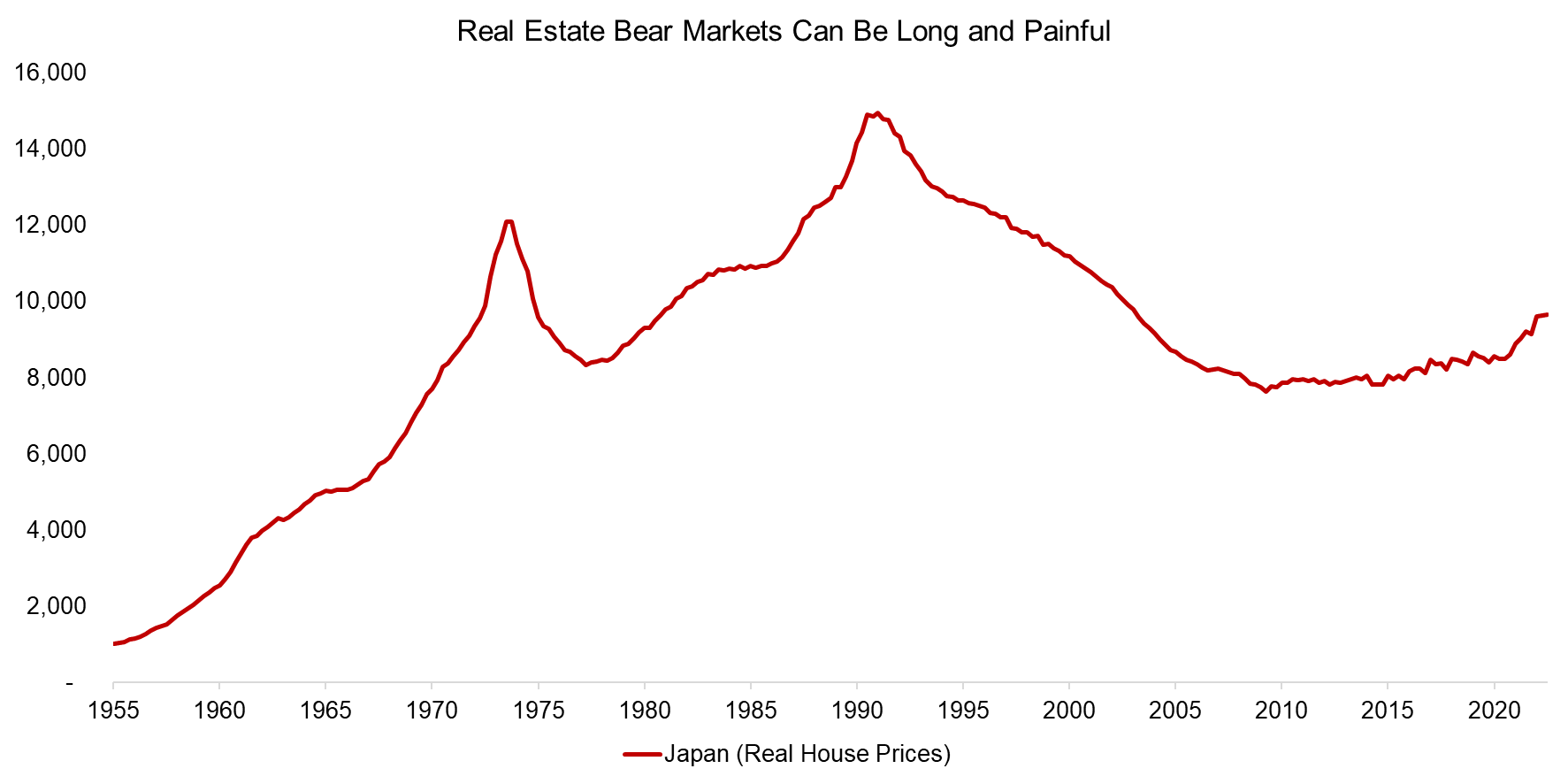

But as in any financial market, such feedback loops can lead to bubbles that are quite painful when they start to deflate. As an ascendant economic powerhouse in the 1980s, Japan experienced a significant boom in home prices during the 1980s, but the subsequent bear market lasted for almost three decades.

Source: BIS, Finominal

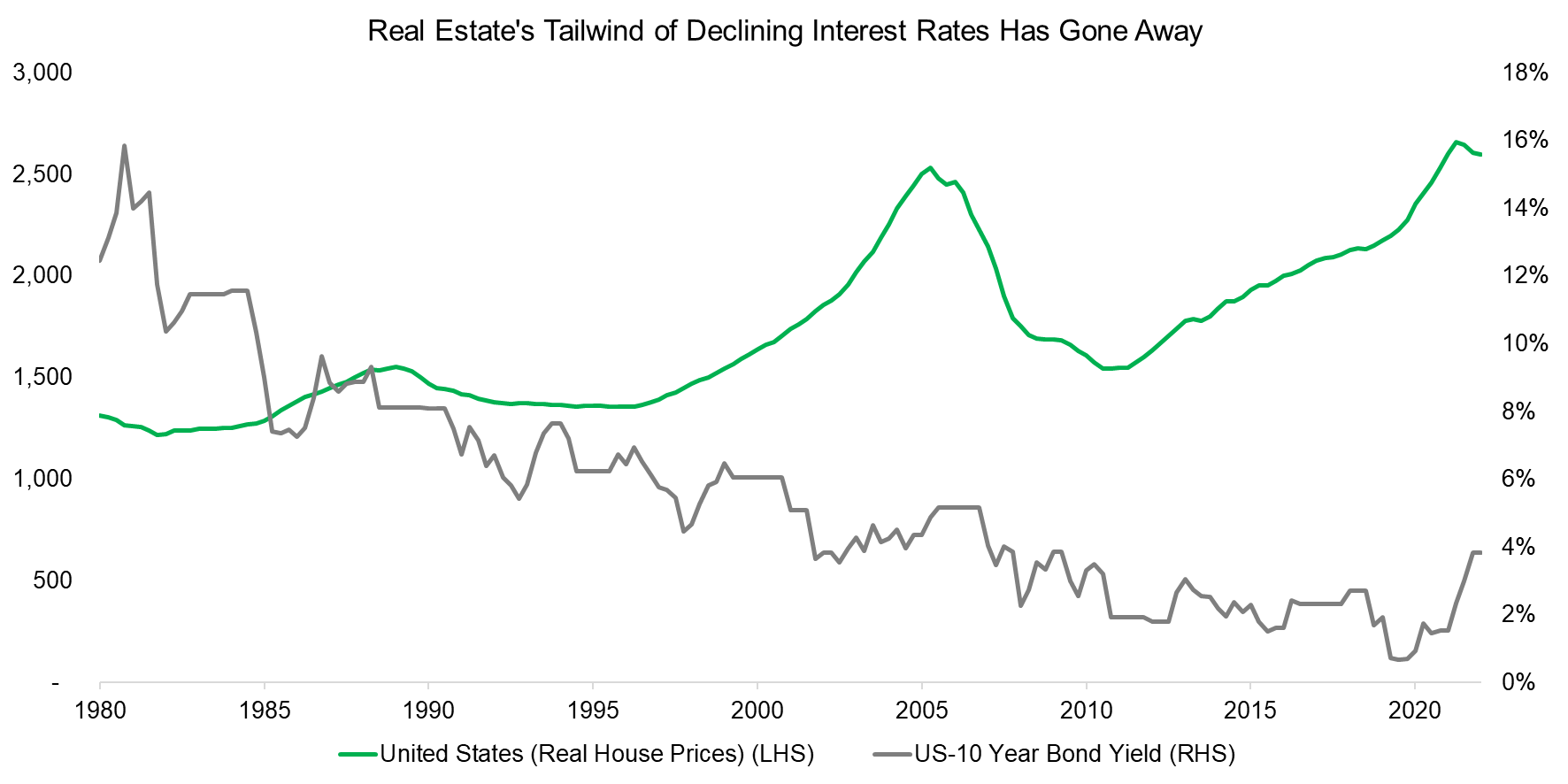

Fiscal and monetary policy can also encourage real estate speculation. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis (GF), the UK government adopted a help-to-buy program that offered interest-free mortgages, and quantitative easing (QE) and other accommodative measures by central banks provided a powerful tailwind for home prices. Interest rates had been on the decline since the 1980s in most developed countries, so both retail and professional investors came to see real estate as an alternative to bonds and shifted trillions in capital from fixed income.

As a consequence, real estate yields reached record lows, with UK homes generating less than 2% per year in rental income before maintenance costs and taxes. As such residential real estate made little sense as an investment — except when compared to equally low or even negative bond yields in some European countries.

With the spike in interest rates over the last two years, however, the pendulum has swung back the other way. Financing home purchases has become much more expensive, and with higher yields in the fixed-income market, owning a home has become even less appealing as an investment.

Source: St Louis FRED, BIS, Finominal

FURTHER THOUGHTS

With the dire outlook for residential real estate, should investors continue to allocate to the asset class?

It is difficult to say in the near term. There are simply too many variables at work. Default rates could spike in residential markets with floating-rate regimes and spur a full-blown real estate crisis. Or not.

Forecasting house prices may be just as futile as forecasting stock prices. In the long-term, those countries with larger demographic challenges like China or Japan are probably best avoided, while those whose populations are expected to grow may be worth exploring. And on that basis, India and Africa stand out, as well as the good old USA for less adventurous investors.

RELATED RESEARCH

Aging & Equities: Selling Stocks for the Long-Term

The Case Against REITs

Factor Investing in Financials, Real Estate & MLPs

Private Equity: Fooling Some People All the Time?

Private Equity: The Emperor has No Clothes

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nicolas Rabener is the CEO & Founder of Finominal, which empowers professional investors with data, technology, and research insights to improve their investment outcomes. Previously he created Jackdaw Capital, an award-winning quantitative hedge fund. Before that Nicolas worked at GIC and Citigroup in London and New York. Nicolas holds a Master of Finance from HHL Leipzig Graduate School of Management, is a CAIA charter holder, and enjoys endurance sports (Ironman & 100km Ultramarathon).

Connect with me on LinkedIn or X.