Monte Carlo Simulations: Forecasting Folly?

What happens in Monte Carlo, should stay in Monte Carlo

January 2024. Reading Time: 10 Minutes. Author: Nicolas Rabener.

SUMMARY

- Financial advisors primarily use Monte Carlo simulations to forecast returns

- However, this methodology is flawed as it ignores the valuations of asset classes

- Using capital market assumptions is likely a better approach

INTRODUCTION

The Shanghai Composite Index (SSE) was booming in early 2015, and as it soared, legions of new investors rushed in to try their luck at securities speculation. Although stock bubbles were nothing new, this one had two peculiarities. First, under the regulatory framework, SSE stocks could not rise or fall more than 10% on any given day, which after several months of a bull market, made for some unusual-looking stock price charts. Second, many retail investors focused on buying “cheap” stocks, or those that traded below 20 renminbi (RMB).

Like all bubbles, this one eventually deflated. The SSE plunged nearly 40% between June and September 2015 and taught many novice investors the difference between price and valuation. A stock trading at $5 may be obscenely expensive just as one that trades at $1,000 may be a steal.

While experienced investors understand this intuitively, many financial advisers are guilty of making similar mistakes. On any given day, they meet with prospective and current clients to discuss their financial outlook. Central to these conversations are forecasts — often in the form of Monte Carlo simulations — that estimate the value of the client’s investment portfolio at their prospective retirement date.

Here is why this is a flawed approach and why there is a better way to anticipate future returns.

EXPECTED RETURNS

Thousands of metrics have been tested across time periods and geographies, but there is no evidence that any investor, even those equipped with artificial intelligence (AI)-powered strategies, can forecast individual stock prices or that of the entire market in the short to medium term (read Hitting Home Runs with AI Investing?). If it were otherwise, mutual fund and hedge fund managers would generate more alpha (read Less Efficient Markets = Higher Alpha?).

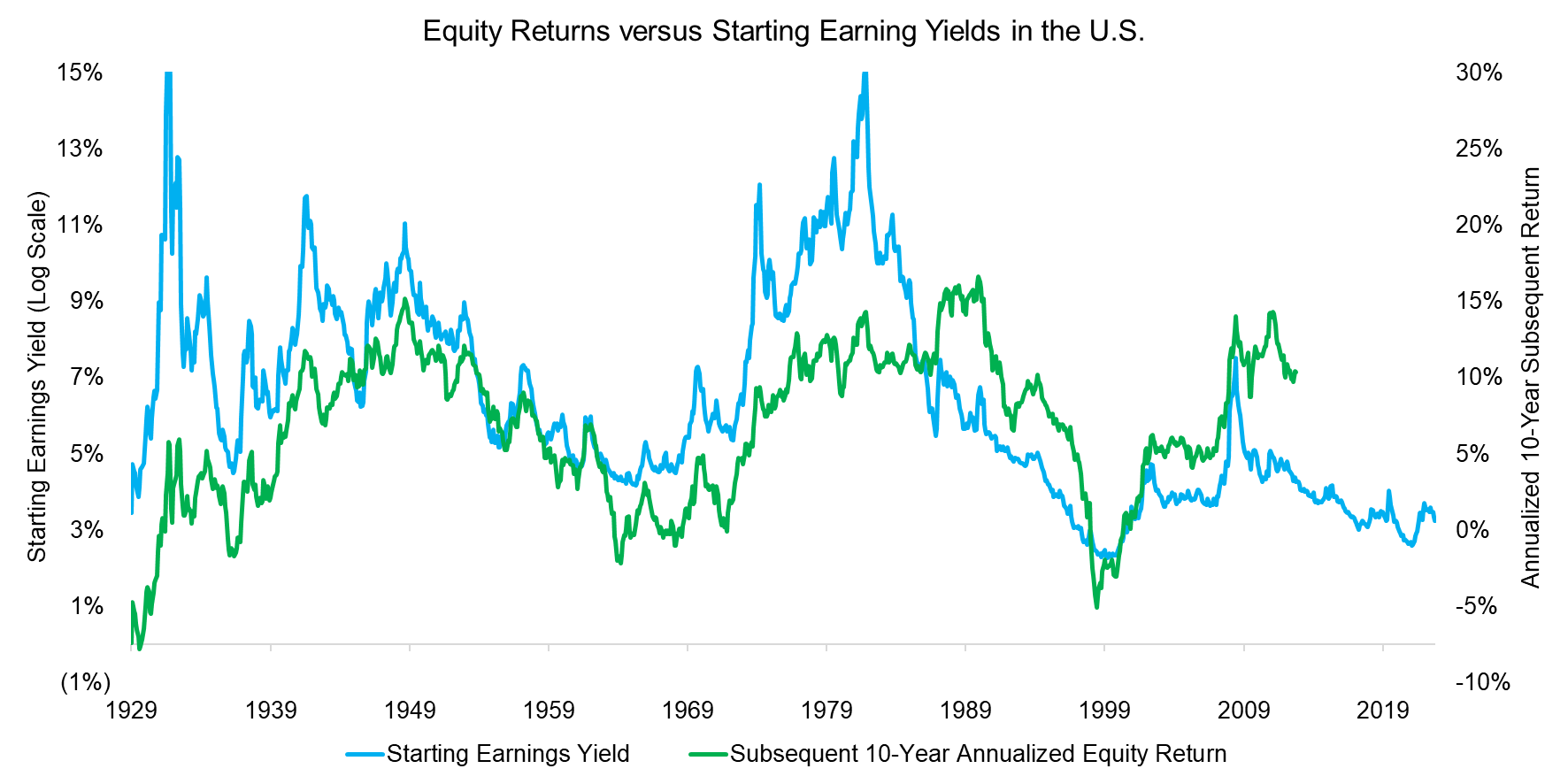

Forecasting the long-term expected returns should be more feasible. Although not a perfect relationship, S&P 500 returns over the next 10 years have tended to reflect the current earnings yield, or the inverse of the price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio. Put another way, valuations matter, and the higher the earnings yield today, the higher the expected returns 10 years from now.

Source: Online Data Professor Robert Shiller, Finominal

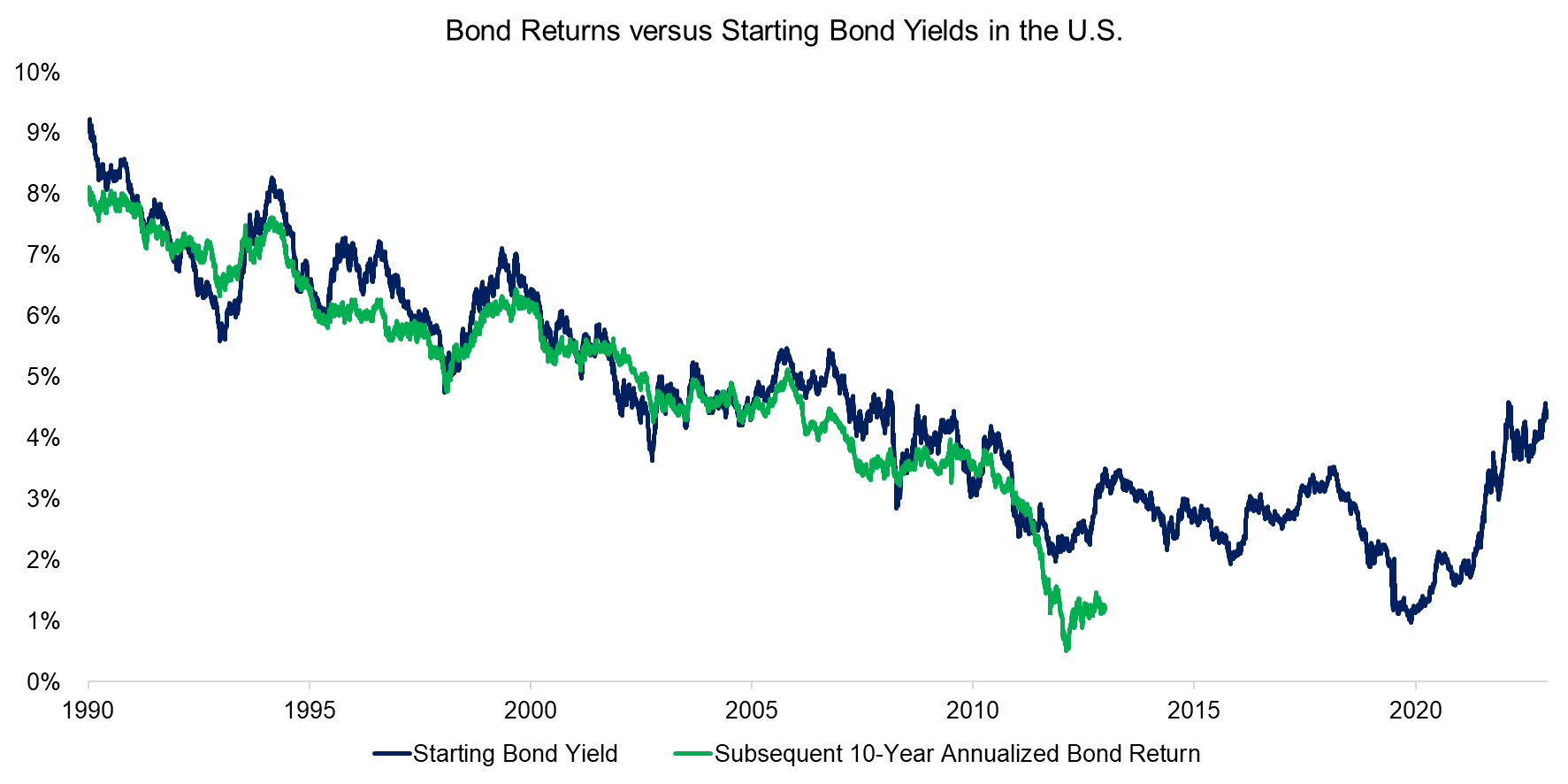

US investment-grade bonds over the last 20 years demonstrate the relationship between expected long-term returns and current valuations even more strongly. The bond’s initial return was the equivalent of the annual return for the next 10 years. For example, if the current bond yield is 2%, then the expected return is likely 2% per year for the next 10 years. So, you get what you pay for.

Source: Finominal

THE FOLLY OF MONTE CARLO SIMULATIONS

Financial advisers rarely use stock and bond market valuations to build their long-term forecasts. Rather they primarily run Monte Carlo simulations that do not consider valuations at all. The inputs for these simulations are historical prices and a few model assumptions, while the output is a range of expected returns with a certain probability and assuming a normal distribution. A portfolio’s range of expected returns may be 13.45%, with a bottom quartile expectation of –0.63% and an upper quartile expectation of 25.71%, given an 85% probability.

Such a result will only confuse most clients, but even if it didn’t, the underlying method is flawed and should not be applied to investment portfolios. All financial products come with the same warning label: Past performance is not indicative of future results. Just because equity markets have gone up for years doesn’t mean they always will.

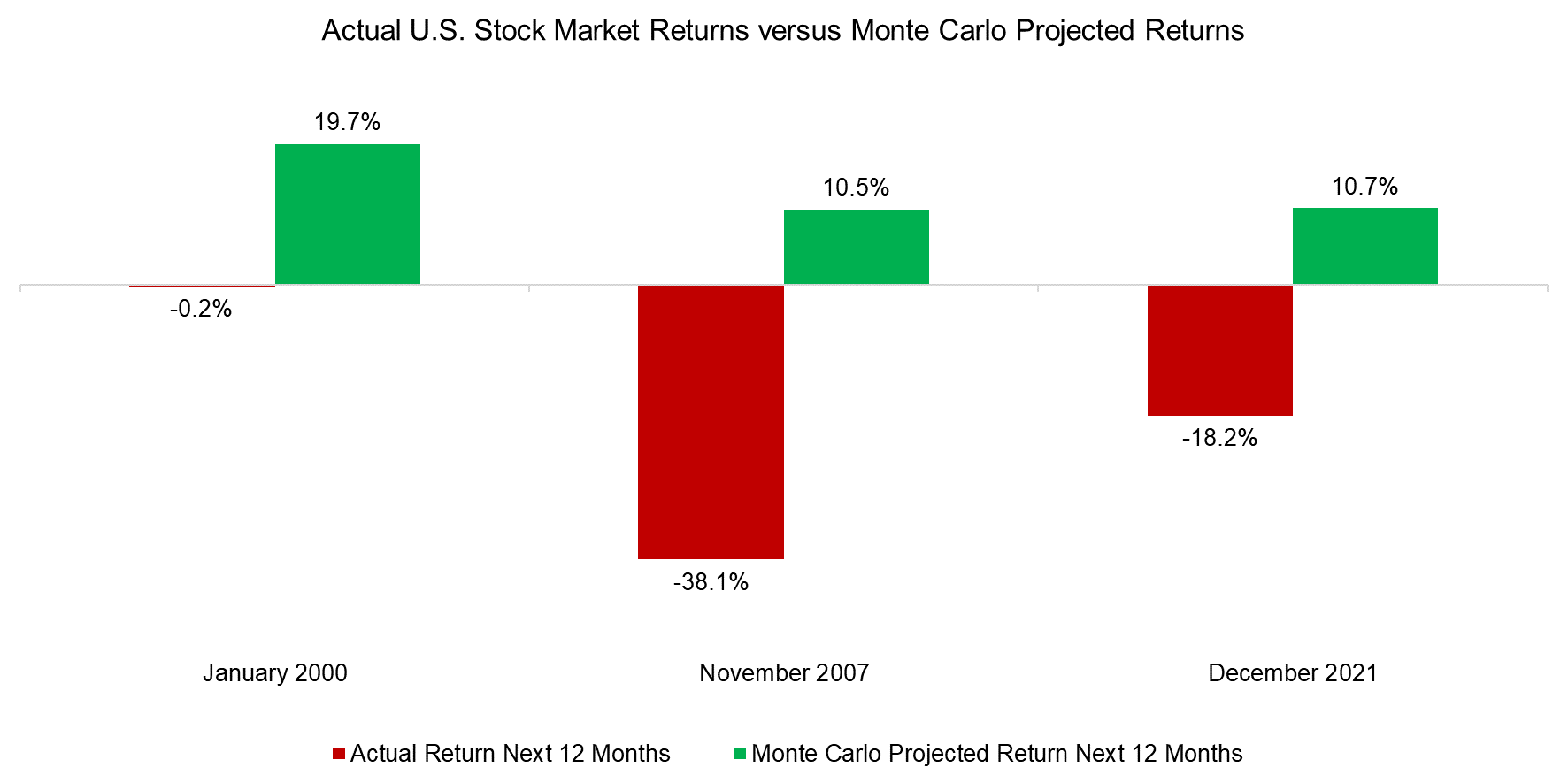

We can cherry-pick a few points in time — January 2000, November 2007, and December 2007, for example — when the S&P 500’s return was miles away from its actual realized return over the next 12 months. Naturally, at these moments, the S&P 500’s P/E ratio reached record levels. But that is not an input for a Monte Carlo simulation.

Source: Finominal

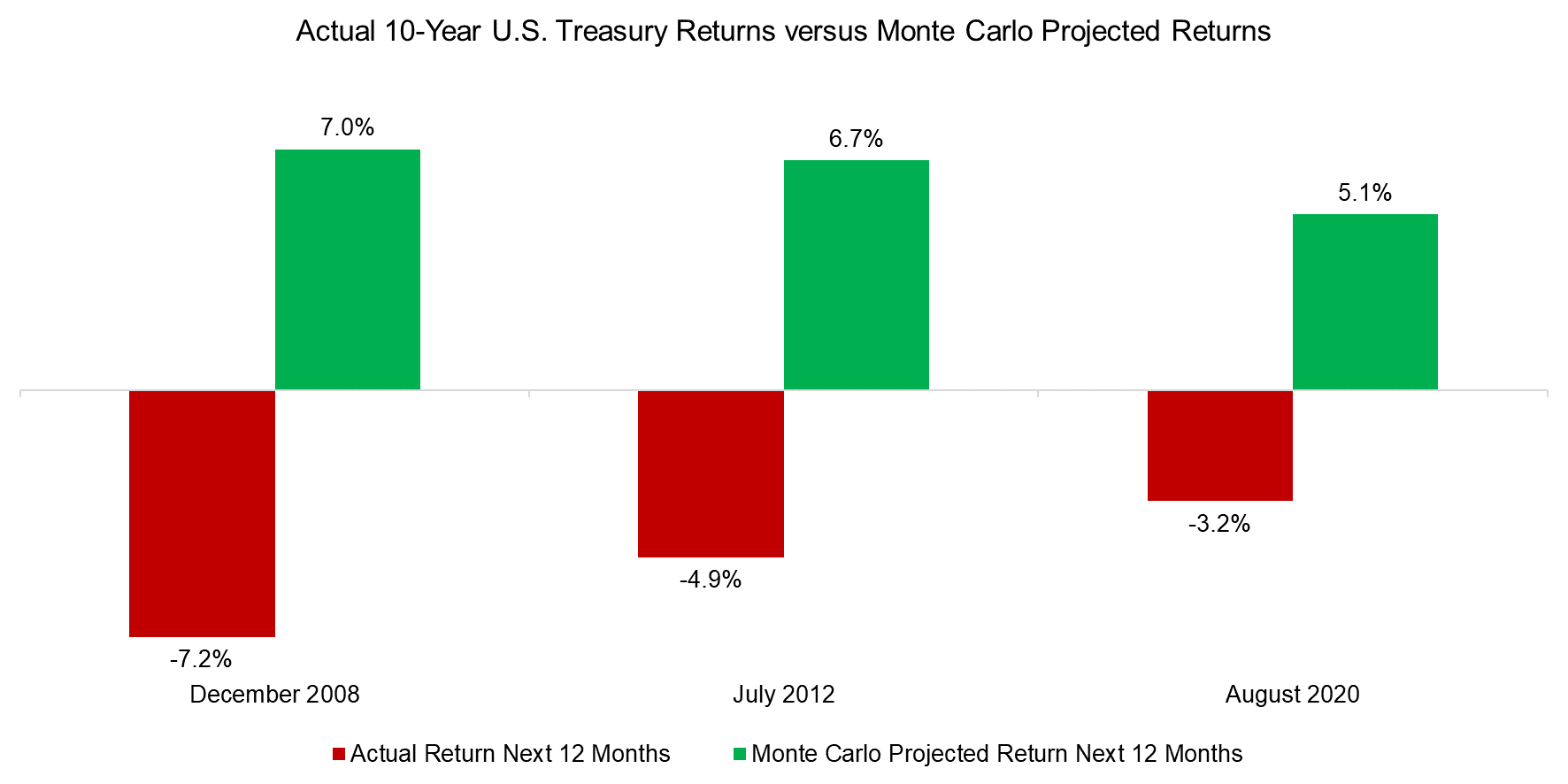

We can select similar periods for US investment-grade bond markets, such as December 2008, July 2012, or August 2020, when yields reached record lows. At those points, Monte Carlo simulations would recall appealing past returns and forecast the same trajectory going forward.

But bonds do become structurally unattractive at certain yields. Yields on European and Japanese bonds went negative during the last five years. But not if we only looked at Monte Carlo simulations based on past performance. Like lemmings running up a cliff, “it’s been a great run, boys, let’s keep the pace….”.

Source: Finominal

CAPITAL MARKET ASSUMPTIONS

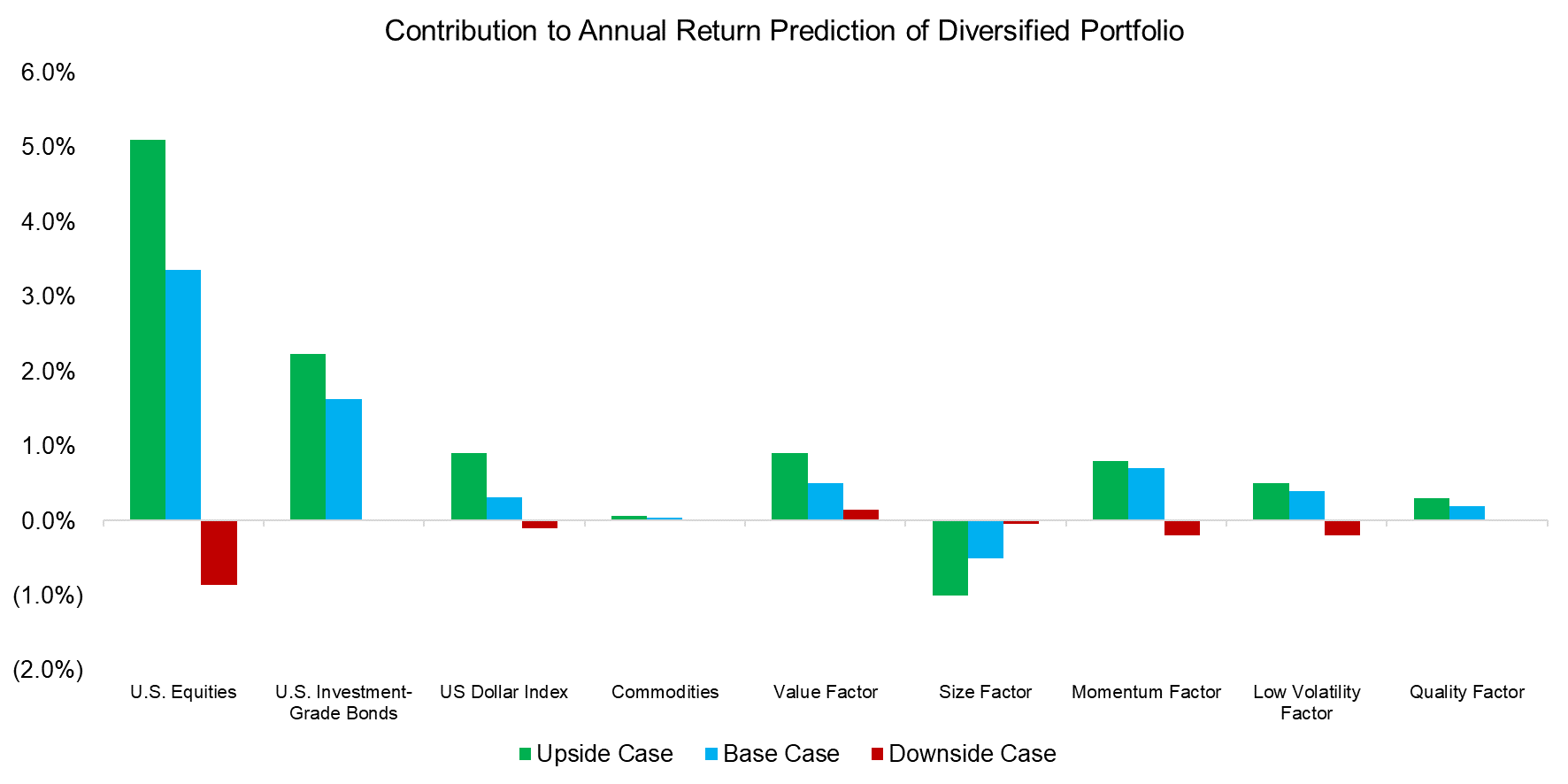

For those forecasting expected returns for an investment portfolio, capital market assumptions are an alternative to Monte Carlo simulations. The process is much simpler and only requires the capital market assumptions, which are available for different asset classes and equity factors from various investment banks and asset managers, and a factor exposure analysis of the portfolio. These can be differentiated into upside, base, and downside cases, so that the forecast delivers a realistic range of outcomes.

Source: Finominal

FURTHER THOUGHTS

Monte Carlo simulations have obvious flaws but so do capital market assumptions. Market analysts and economists alike have a poor track record when it comes to generating accurate forecasts. If they were good at it, they would be fund managers making money off their predictions. As it is, no fund manager can time the market with any consistency.

But asset managers rely heavily on valuations when creating their capital market assumptions, so they may be preferable to simplistic Monte Carlo simulations based on past performance. Whatever the method, the forecasts will inevitably be wrong, but one approach is slightly more foolish than the other.

RELATED RESEARCH

Market Timing with Multiples, Momentum & Volatility

Market Timing vs Risk Management

The Mirage of Direct Indexing

Myth-Busting: The Economy Drives the Stock Market

Myth-Busting: Earnings Don’t Matter Much for Stock Returns

Myth-Busting: Low Rates Don’t Justify High Valuations

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nicolas Rabener is the CEO & Founder of Finominal, which empowers professional investors with data, technology, and research insights to improve their investment outcomes. Previously he created Jackdaw Capital, an award-winning quantitative hedge fund. Before that Nicolas worked at GIC and Citigroup in London and New York. Nicolas holds a Master of Finance from HHL Leipzig Graduate School of Management, is a CAIA charter holder, and enjoys endurance sports (Ironman & 100km Ultramarathon).

Connect with me on LinkedIn or X.