Does Financial Leverage Make Stocks Riskier? Part II

Or asked differently, can companies boost returns via leverage?

March 2021. Reading Time: 10 Minutes. Author: Nicolas Rabener.

SUMMARY

- The most leveraged stocks were not riskier than the least leveraged ones on a cross-sector basis

- However, this changes when portfolios are created sector-neutral

- In this case, the least leveraged stocks also generated higher returns and risk-return ratios

INTRODUCTION

Most investors assume that higher risk is rewarded with higher returns. Take the equity risk premium as an example, which contains risk as well as premium in its name. It implies that the risk from owning equities is compensated with a premium, compared to zero-risk investments like cash.

However, within equities, the relationship between risk and return is not linear. The Low Volatility factor is academically well established and documents that more volatile stocks do not outperform less volatile ones, at least on a risk-adjusted basis.

Some investors might argue that volatility does not equate to risk, but taking a different metric like financial leverage yields similar results. We recently highlighted in a research note that the most leveraged stocks in the US did not outperform the least leveraged ones between 1980 and 2018.

Having said this, taking leverage as a measure of risk can also be challenged as companies from certain sectors like utilities can sustainably carry higher leverage than others given predictable cash flows. Perhaps the reason for the lack of outperformance of more leveraged stocks is simply due to certain sector biases.

In this short research note, we will analyze the impact of leverage on the risk and return of US stocks on a sector-neutral basis (read Does Financial Leverage Make Stocks Riskier?).

FINANCIAL LEVERAGE ACROSS SECTORS

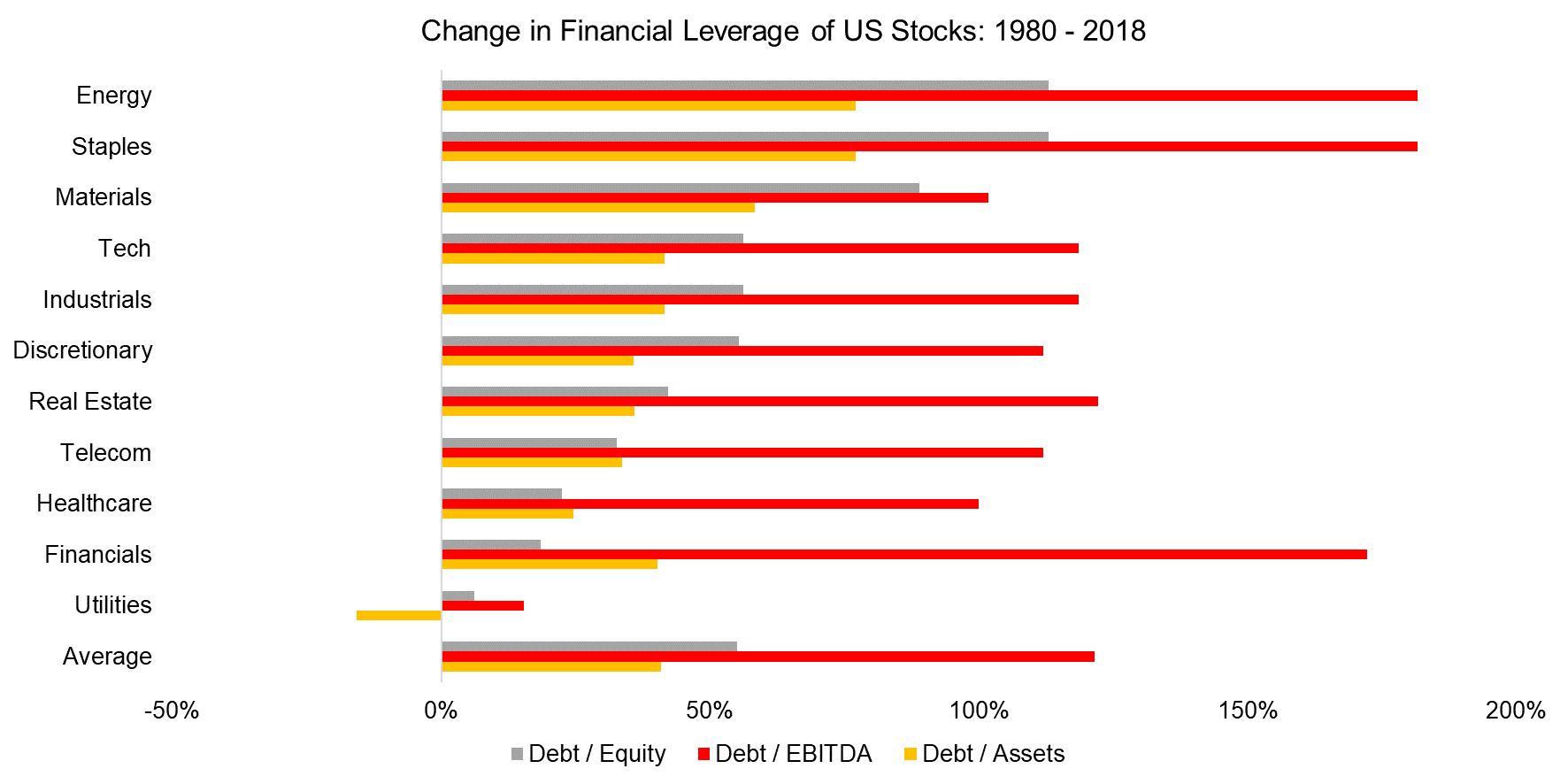

In this analysis, we are focusing on all companies listed in the US stock market in the period between 1980 and 2018 and measure their financial leverage by three metrics: debt-over-equity, debt-over-assets, and debt-over-EBITDA. Specifically, we focus on the 10% most and least leveraged stocks.

We observe that listed US companies increased their leverage across sectors over the last four decades, although the magnitude depends on the chosen metric. Companies have become 50% more leveraged on average when measured on debt-over-equity and debt-over-assets, but more than 100% when using debt-over-EBITDA. Given that debt is the same amount in the calculation for all three metrics, this implies less growth in EBITDA than in total assets or equity. One explanation for this is the structural consolidation in the US economy that frequently leads to the creation of goodwill. EBITDA is not impacted by goodwill, but it does increase total assets and equity.

Source: FactorResearch

HIGHER LEVERAGE, HIGHER RISKS?

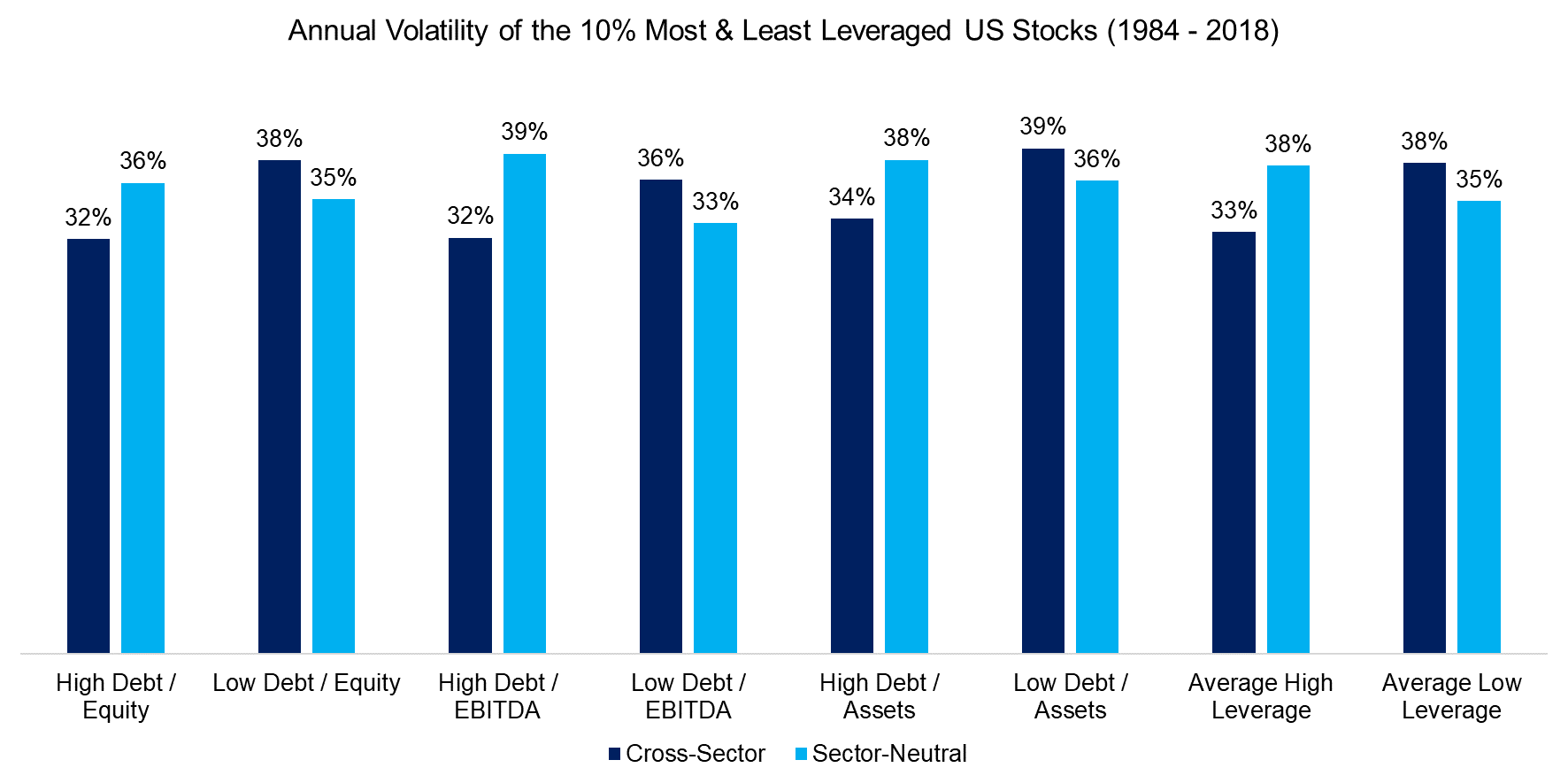

First, we will contrast the risk as measured by the 12-month stock price volatility on a cross-sector and sector-neutral basis. We observe that the most leveraged stocks were less volatile than the least leveraged ones on average when ignoring sectors, which is counter-intuitive as leverage is typically associated with riskiness.

However, this is simply explained by sector biases, e.g. utility stocks can be highly leveraged, but that does not make them volatile stocks given the stable characteristics of their industry. And indeed, on a sector-neutral basis, the most leveraged stocks were more volatile than the least leveraged ones.

Source: FactorResearch

It is worth noting that the risks of leverage have likely been understated during the observation period as interest rates have continuously been declining since the 1980s. Many highly indebted companies avoided a restructuring or bankruptcy filing as they have been able to continuously refinance maturing debt at lower rates. Naturally, this will be more challenging going forward as interest rates have reached their natural floor (read Myth-Busting: Low Rates Don’t Justify High Valuations).

MORE LEVERAGE, MORE RETURN?

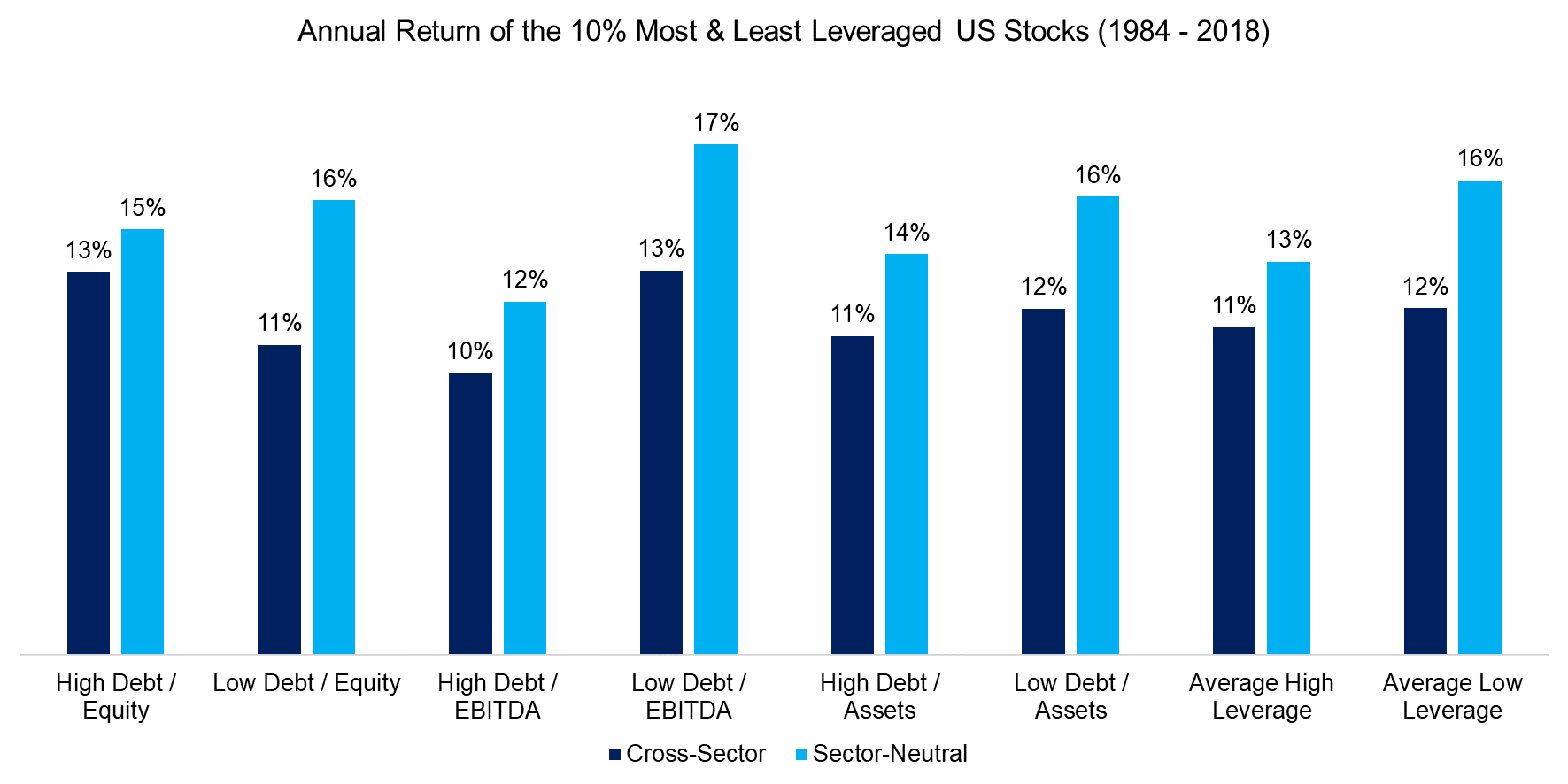

Given that we have now established a more intuitive relationship between leverage and risk, we can turn to the question if investors are rewarded by higher returns for accepting higher risks (leverage). Interestingly, neither on a cross-sector nor on a sector-neutral basis was this the case. Corporate management and investors frequently argue that balance sheets should be leveraged for boosting shareholder returns, but this is not supported by this analysis.

It is worth noting that in some asset classes like real estate and private equity leverage plays a critical role in the mindsets of the participants. However, given that there is no linear relationship between leverage and returns in equities, it is questionable why that should be different in those asset classes.

Source: FactorResearch

ANALYZING RISK-ADJUSTED RETURNS

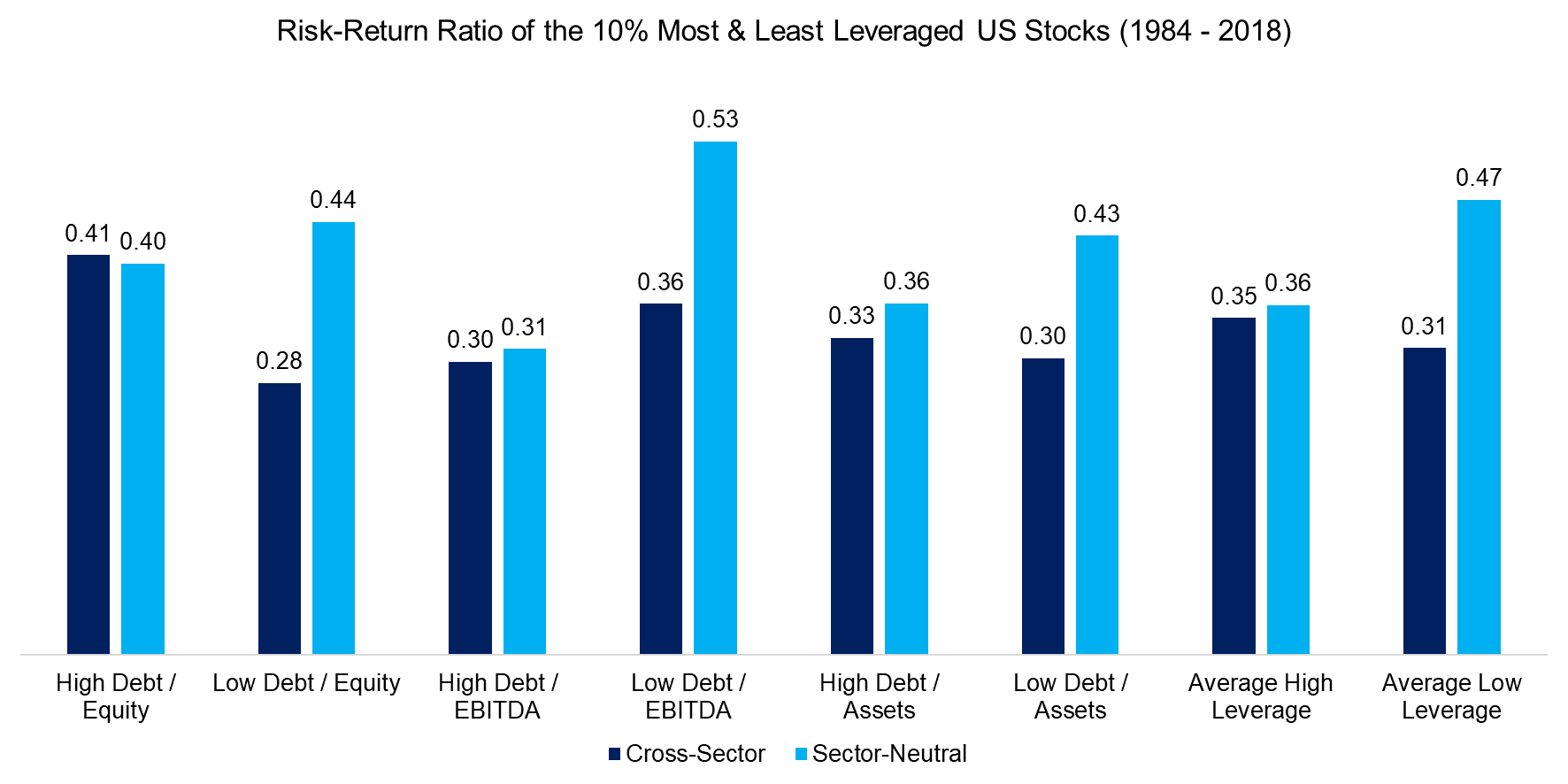

When calculating the risk-adjusted returns, the conclusion on the lack of value creation via leverage crystalizes further as the stocks with the lowest leverage generated far higher risk-return ratios than the most leveraged stocks on a sector-neutral basis. Given this, investors should avoid stocks with too much leverage, especially sector specialists.

Source: FactorResearch

FURTHER THOUGHTS

Debt per se is not negative and it allows companies to invest, hopefully into projects that will generate revenues and profits. However, when the economic growth is declining then leverage makes companies financially less flexible and increases their bankruptcy risk.

This author used to manage a portfolio of REITs, which is a sector where companies tend to be highly leveraged. The CEOs of REITs frequently argued during management meetings that they would increase debt when the economy would be growing and pay it back when the outlook worsened, but that is naturally a foolish assumption. If executives could predict market cycles, then they would work at global macro funds. Given that these have not generated much alpha in well over a decade, highlights the challenges of predicting markets.

Furthermore, even industries with highly predictable cash flows can face crises that might threaten their livelihood. For example, prime shopping center and office REITs were seen as difficult to disrupt at the beginning of 2020, but the global pandemic has destroyed this assumption pretty quickly.

RELATED RESEARCH

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nicolas Rabener is the CEO & Founder of Finominal, which empowers professional investors with data, technology, and research insights to improve their investment outcomes. Previously he created Jackdaw Capital, an award-winning quantitative hedge fund. Before that Nicolas worked at GIC and Citigroup in London and New York. Nicolas holds a Master of Finance from HHL Leipzig Graduate School of Management, is a CAIA charter holder, and enjoys endurance sports (Ironman & 100km Ultramarathon).

Connect with me on LinkedIn or X.