Portfolio Construction in Venture Capital

Lessons from public markets

May 2021. Reading Time: 10 Minutes. Author: Nicolas Rabener.

SUMMARY

- A few winners generate most of the venture capital returns

- Given this asymmetrical return distribution, portfolios should be constructed equally

- Missing the winners is simply too risky

INTRODUCTION

2020 turned out to be a record year for the venture capital industry, despite the global pandemic. More than 12,000 investments were made into early to late-stage start-ups at a combined value of $166 billion, according to data from PitchBook. 2021 started even better due to the boom in IPOs, SPACs, and direct listings, which created substantial wealth for the founders and business angels of companies like CoinBase or Roblox that went public. Many of these early investors are now thinking of compounding their newly created wealth by becoming venture capitalists themselves.

However, becoming a successful venture capitalist requires more than just having money. Setting up the legal structures is relatively straightforward, but access to deals is critical for achieving returns better than what the stock market offers. Fortunately, having created or made money by investing in start-ups that became public companies, which is often the ultimate dream when building a business in a garage, makes such first-time venture capitalists attractive to the next generation of founders (read Venture Capital: Worth Venturing Into?).

Another challenge is to create a sound asset allocation framework. Investments in start-ups can be weighted by the venture capitalist’s conviction, or equally. In practice, it is also a function of the deal flow and the financing requirements of start-ups.

There is no data on venture capital investments publicly available that allows analyzing these two allocation frameworks, but we can use public markets data to do so. It will not be an apples-for-apples comparison, but it will hopefully provide food for further thoughts. In this research note, we will muse on how to optimally construct a venture capital portfolio.

PUBLIC MARKET DATA AS A PROXY

We will use US-based biotech stocks as proxies for venture capital investments. These stocks are highly risky and many of them go into bankruptcy, mostly when their drugs do not get regulatory approval as they fail to provide the desired results or produce unacceptable side effects in patients.

However, a few of the companies succeed and launch products that typically result in significant increases in their revenue. It might be years of research and development, but the returns to investors for successful drug commercialization can be substantial.

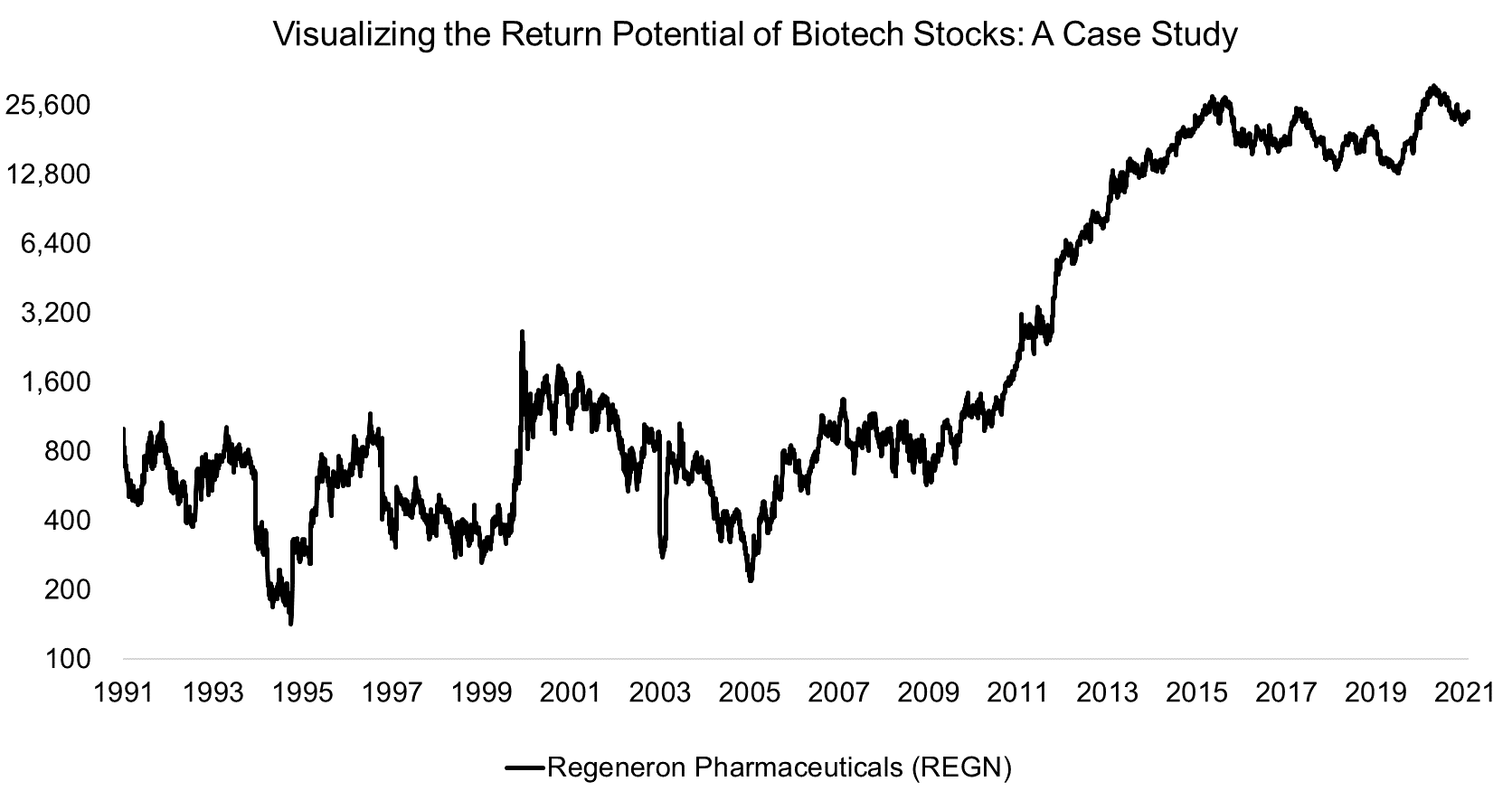

We can visualize this hockey-stick pay-off profile of biotech stocks via the performance of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals (REGN). The stock generated essentially flat returns between 1991 and 2010, and declined by more than 50% multiple times during that time period. As the path of most entrepreneurs, it was a painful and mostly disappointing journey.

The pay-off for investors in Regeneron started in 2011 as the stock price increased by multiple times thereafter. The company announced a new drug that would significantly reduce cholesterol in collaboration with the pharma giant Sanofi. Further joint ventures followed, fueling the enthusiasm of shareholders.

Although Regeneron has ultimately paid off for its investors, it is unlikely that many of the original investors from 1991 were still invested. It would have required almost inhuman patience and the ability to suffer substantial drawdowns. Given that such return distributions are typical for start-ups, what is the best allocation framework for investing in such risky companies?

Source: FactorResearch

EQUAL VERSUS MARKET CAP-WEIGHTING INVESTMENTS

Some venture capitalists are always allocating the same amount of capital, regardless of their conviction into the attractiveness or the funding needs of a start-up. $100,000 checks – come rain or shine. Essentially, these investors are pursuing an equal-weighted asset allocation strategy.

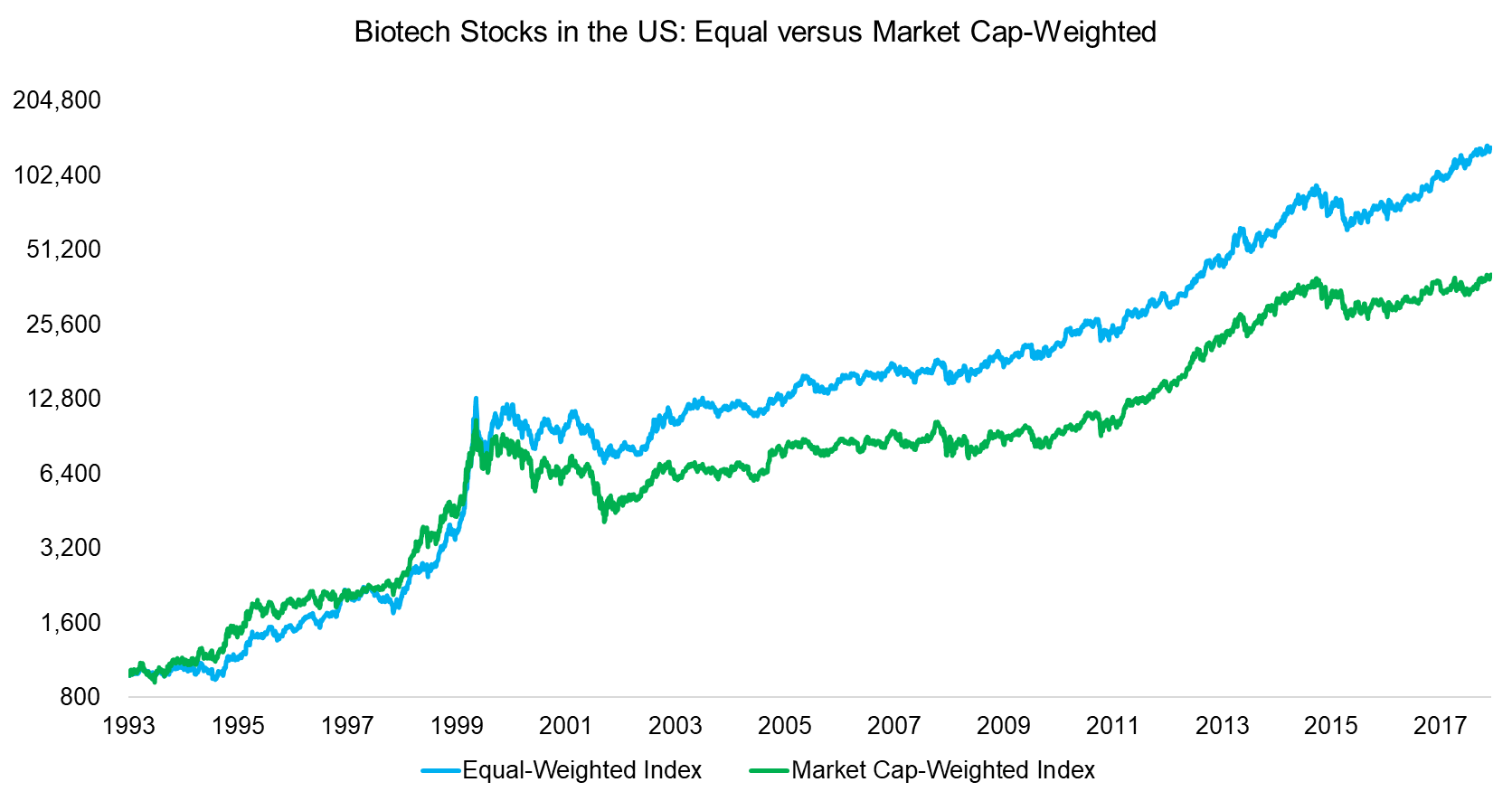

We can simulate this strategy using biotech stocks in the US and contrast an equal-weighted portfolio with a market capitalization-weighted one. We only consider biotech stocks with a market capitalization of above $500 million, which creates a universe of almost 250 stocks. The analysis highlights the same trends in performance in the period between 1993 and 2018, albeit significantly higher returns when maintaining equal weights.

However, we need to highlight that although venture capitalists can allocate the same amount of capital into start-ups, compared to a fund manager investing in stocks, rebalancing is often impossible. Private shares are difficult to trade and liquidity events rare.

Source: FactorResearch

THE RISK OF MISSING WINNERS

Most investors are unaware that almost all of the stock market returns are explained by a minority of stocks. The majority of stocks contribute zero or negative returns to indices like the S&P 500. In recent years, this has been the FAANMG stocks and if these are excluded, then the performance of the S&P 500 is significantly lower.

In contrast, venture capitalists are keenly aware of this asymmetrical return distribution. The general rule is that out of ten start-up investments, seven can be written off, two will produce zero returns and only return the initial investment, and only one will become a large and profitable company that generates stellar returns for its backers.

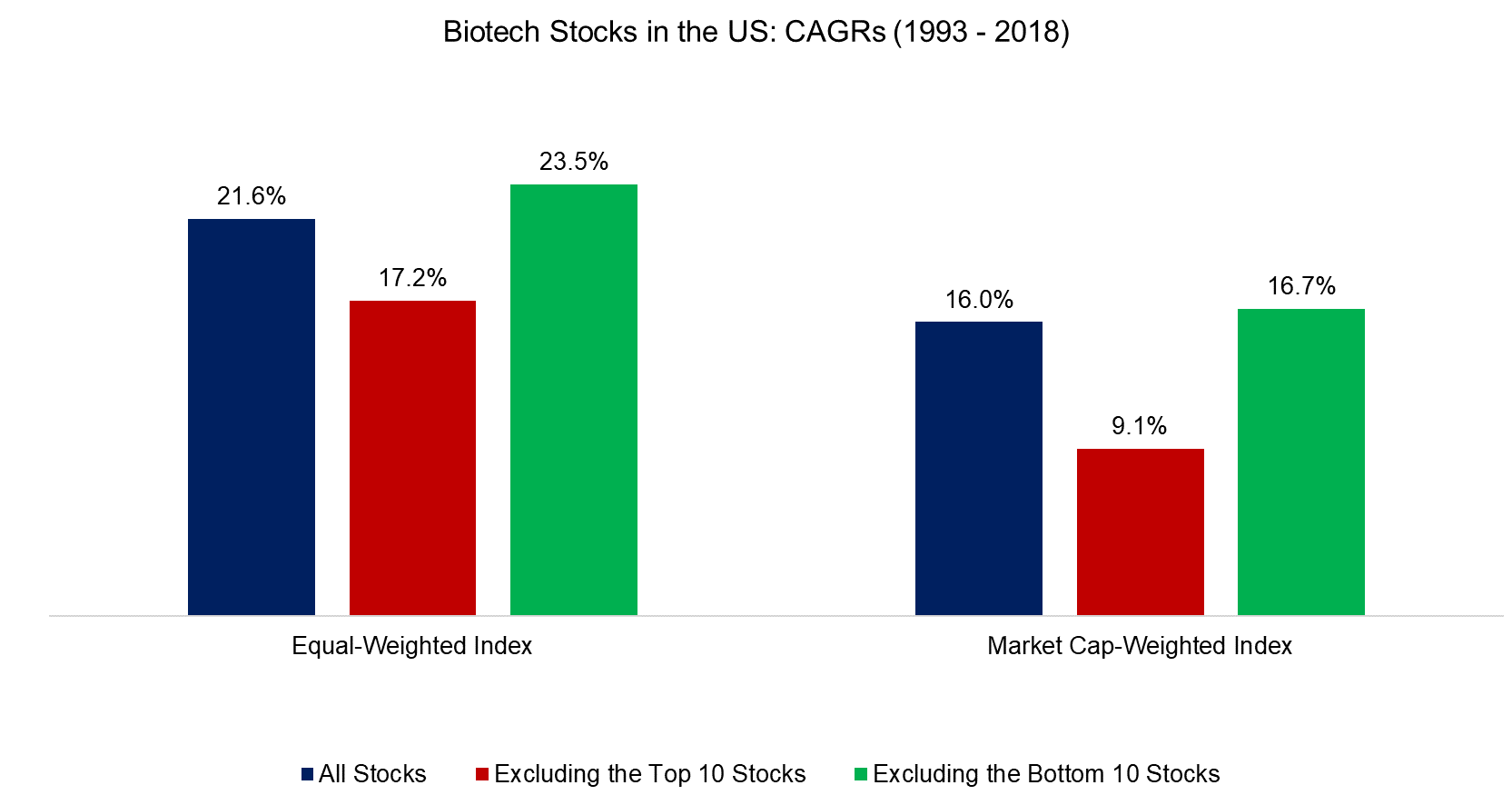

We can visualize these return distribution characteristics by calculating the returns of the equal- and market-weighted biotech indices while excluding the ten best performing and the ten worst performing stocks over the almost 30-year period. This scenario analysis highlights that excluding the top 10 stocks slightly decreased the annual return of the equal-weighted portfolio, but had a significantly more negative impact on the market cap-weighted portfolio.

Even more interesting, excluding the worst-performing stocks had a lower impact on returns than excluding the best-performing stocks. It is all about the winners. Missing these would have cost investors dearly.

Source: FactorResearch

FURTHER THOUGHTS

Most fund managers and venture capitalists will likely respond to this analysis by stating as long as they can identify the winners, all is good. Unfortunately, the empirical evidence shows that mutual fund managers, hedge fund managers, and even private equity fund managers are unable to generate any alpha, i.e. able to pick the winners. Especially on a consistent basis. Markets have become too efficient and information asymmetries have been arbitraged away (read Private Equity: The Emperor has No Clothes).

In contrast, some venture capitalist funds are still able to generate high excess returns with consistency. However, this is explained by the managers of these funds having such a reputational pull that they have a proprietary deal flow that allows them to generate stellar returns. Although this is great, it only applies to a few individuals, who are mostly based in Palo Alto. The average venture capital fund generates the same returns as a technology index like the Nasdaq.

For first-time venture capitalists who are building their personal brand and are unlikely to have access to the best start-ups, there is a substantial risk of missing the winners and generating less attractive returns than public equities. It might be better to invest in certain themes but then allocate equally across these as much as possible.

RELATED RESEARCH

Private Equity: Fooling Some People all the Time?

REFERENCED RESEARCH

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nicolas Rabener is the CEO & Founder of Finominal, which empowers professional investors with data, technology, and research insights to improve their investment outcomes. Previously he created Jackdaw Capital, an award-winning quantitative hedge fund. Before that Nicolas worked at GIC and Citigroup in London and New York. Nicolas holds a Master of Finance from HHL Leipzig Graduate School of Management, is a CAIA charter holder, and enjoys endurance sports (Ironman & 100km Ultramarathon).

Connect with me on LinkedIn or X.