Smart Beta: Broken by Design?

Investors Can’t Have Their Cake and Eat It Too

February 2019. Reading Time: 10 Minutes. Author: Nicolas Rabener.

SUMMARY

- Smart beta excess returns are different from factor returns

- The Low Volatility factor shows the highest discrepancy between theoretical and realized returns

- Investors might be better served by embracing long-short factor products

REALITY DYSFUNCTION

Steve Jobs’s “reality distortion field” warped Apple employees’ perception of what was technically possible. Though it led to many internal conflicts, it also drove Apple to create world-changing products like the iPhone.

Finance has reality distortion fields of its own: Providers help redefine investors’ expectations of what particular investment strategies can deliver. Smart beta has an especially strong reality distortion field. Academic research detailing the benefits of factor investing strategies has helped persuade investors to allocate more than $1 trillion to smart beta products.

But the scholarship motivating these allocations largely ignores transaction costs that reduce returns significantly. Furthermore, factor portfolios and smart beta products have different portfolio construction methods, so realized returns from investable products might differ considerably from the theoretical returns.

All of this begs the question: Is smart beta broken by design? (read Smart Beta or Smart Marketing)

THE RISE OF SCIENTIFIC INVESTING

Many scientists have been lured to Wall Street in recent decades. Often they join financial institutions and produce research papers showcasing the attractive risk-adjusted returns generated by innovative quantitative strategies.

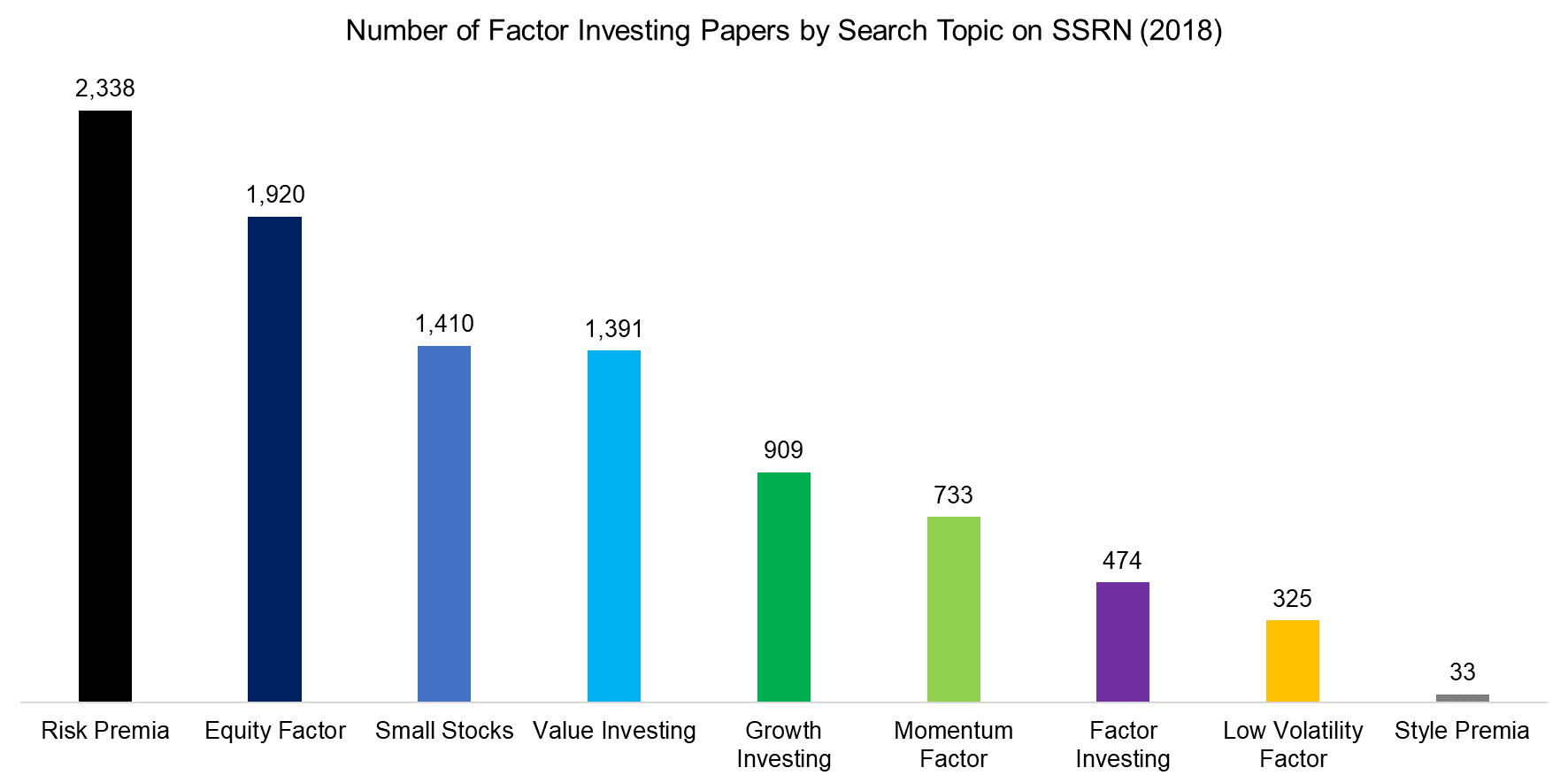

Over time, these PhDs have produced a flood of papers on factor investing, which provides the theoretical foundation of smart beta allocations.

Source: SSRN, FactorResearch

THEORY VERSUS REALITY

But constructing factor portfolios in academic research is much different than building investable smart beta exchange-traded funds (ETFs). At a high-level, factor portfolios represent long-short baskets of stocks ranked by a particular factor, while smart beta ETFs are simply index products with factor tilts (read ETFs, Smart Beta & Factor Exposure).

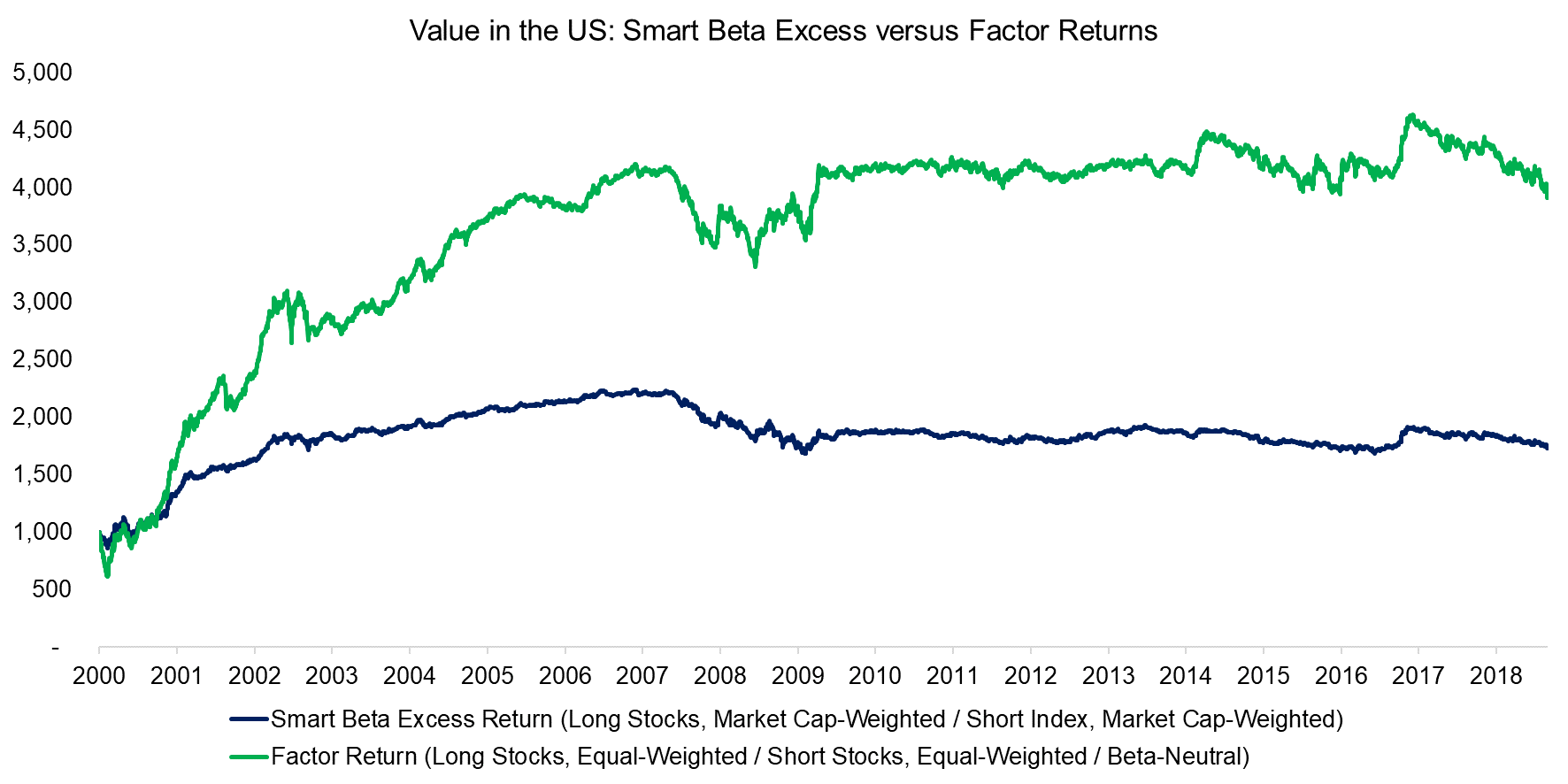

The Value factor is created by buying cheap companies and selling expensive ones, for example, and its US iteration offers a compelling case study. Stocks are selected through a combination of price-to-book and price-to-earnings multiples. To compare smart beta and factor returns, we calculate the excess returns of the former by shorting the index.

Though the trends are similar, the long-short Value factor outperformed smart beta. So investors looking to capture factor returns based on the research would likely be disappointed by the much lower excess return generated by smart beta.

Source: FactorResearch

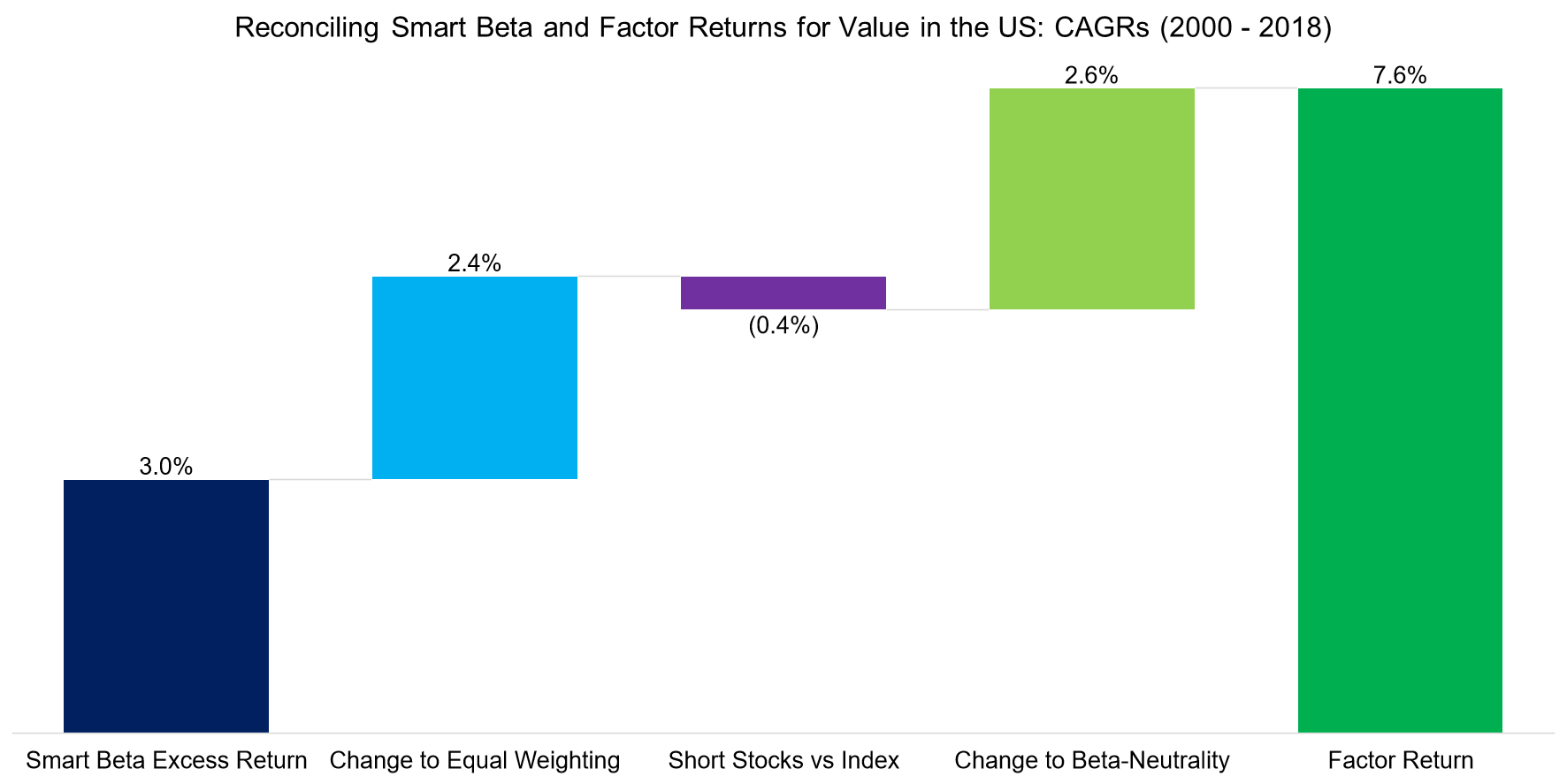

We can reconcile the smart beta and factor returns by demonstrating the differences in how the portfolios were constructed:

- We created smart beta portfolios by selecting the 30% of all stocks with market caps in excess of $1 billion and ranked most favorably by a factor. Stocks are weighted by market capitalization and excess returns are calculated by shorting the stock market index.

- We then changed the weighting to equal weighting. The indices are typically weighted by market capitalization, which effectively represents a short position in the Size factor. If small caps outperform large caps, which they do over the long term, then an equal weighting will be more favorable for returns.

- Next we short stocks instead of the index, so the short portfolio of a factor is as much a profit center as the long portfolio.

- We then moved from dollar-neutrality to beta-neutrality. Some factors have temporary or structural negative net betas, which lowers returns as markets are rising over the long term. Structuring a portfolio beta-neutral reduces the performance drag.

- We finally calculate the factor return, deriving it from a long-short beta-neutral of the top and bottom 30% of stocks ranked by a factor, with the stocks weighted equally.

These methodological differences do not necessarily need to be accretive for returns. In Value’s case, shorting stocks has not bolstered returns since 2000. This is probably due to the strong performance of Amazon, Netflix, and other Growth stocks in recent years.

Source: FactorResearch

These returns reflect transaction costs, but not management fees, operating expenses, or costs for borrowing shares. Accounting for such expenses would lower returns.

SMART BETA VERSUS FACTOR RETURNS IN THE US

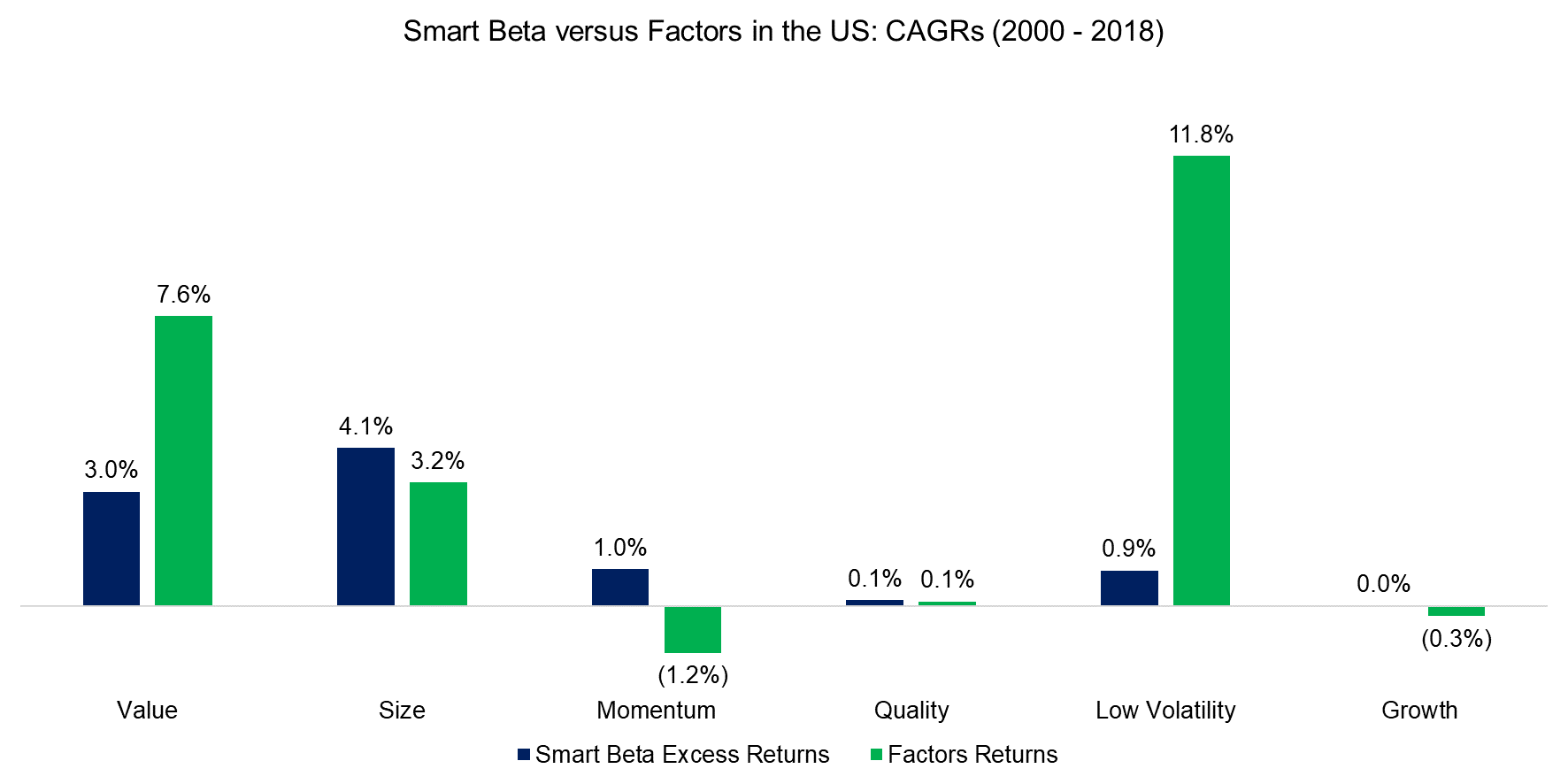

When we expand the analysis from the Value factor to other common equity factors in the US stock market, smart beta and factors showed comparable performance. In some cases – Value, for example – the factor outperformed smart beta. With the Momentum factor, among others, the academic portfolio generated lower returns.

Source: FactorResearch

The Low Volatility factor shows the largest variation between smart beta excess and factor returns. The factor’s premise is that less volatile stocks outperform their more volatile counterparts on a risk-adjusted basis. The downside is that less volatile stocks have lower betas. That means Low Volatility portfolios underperform in bull markets. The long-short factor portfolio adjusts for this by rendering the portfolio beta-neutral, which is not the case for smart beta.

Because of this, investors should adjust their expectations of Low Volatility smart beta ETFs. Given low betas, such products might still preserve capital better than other strategies in down markets, but the expected excess returns will be significantly lower than those highlighted in the research papers.

FURTHER THOUGHTS

Smart beta will disappoint some investors, but that’s as much their fault as the product providers. Investors do not appreciate the significant tracking errors relative to their benchmarks. This has led ETF issuers to create index products with only slight factor tilts. Given the higher price tag of smart beta ETFs compared to plain-vanilla equity ETFs, they are probably not worth the higher fees.

Investors should embrace products with higher factor exposure even if it means higher tracking error. Outperformance will be challenging otherwise. Investors can’t have their cake and eat it too.

If investors are committed to replicating the factor investing returns found in the academic research, they should aim to capture these as efficiently as possible. Harvesting such returns has become easier in recent years as more long-short multi-factor products — liquid alternative mutual funds and even ETFs, among them — have emerged.

Naturally, this implies investing in products that behave much differently than the overall market. But that is a benefit, not a defect.

RELATED RESEARCH

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nicolas Rabener is the CEO & Founder of Finominal, which empowers professional investors with data, technology, and research insights to improve their investment outcomes. Previously he created Jackdaw Capital, an award-winning quantitative hedge fund. Before that Nicolas worked at GIC and Citigroup in London and New York. Nicolas holds a Master of Finance from HHL Leipzig Graduate School of Management, is a CAIA charter holder, and enjoys endurance sports (Ironman & 100km Ultramarathon).

Connect with me on LinkedIn or X.