The Case Against Factor Investing

Long Live Plain Beta?

May 2020. Reading Time: 10 Minutes. Author: Nicolas Rabener.

SUMMARY

- Factor investing is likely the best option for investors seeking to outperform the market

- However, the cyclicality of factors makes factor investing challenging when it underperforms

- Investors that do not understand this cyclicality are likely better served by plain, rather than smart beta

FREE AIN’T EASY

Free and easy are concepts that often go hand-in-hand. However, there are also many instances where free does not equate to easy. Technology and innovation have made investing free as investors can buy core equity ETFs that feature zero management fees and use mobile apps like Robinhood that charge no trading commissions.

However, making good investment decisions is still very hard. The DALBAR investor behavior study for 2018 highlights that the average retail investor in the US lost 9.42% in equity funds, compared to a decline of 4.38% in the S&P 500, which is explained by poor market timing decisions (or put in more precise terms, as the difference between dollar-weighed returns and buy and hold returns).

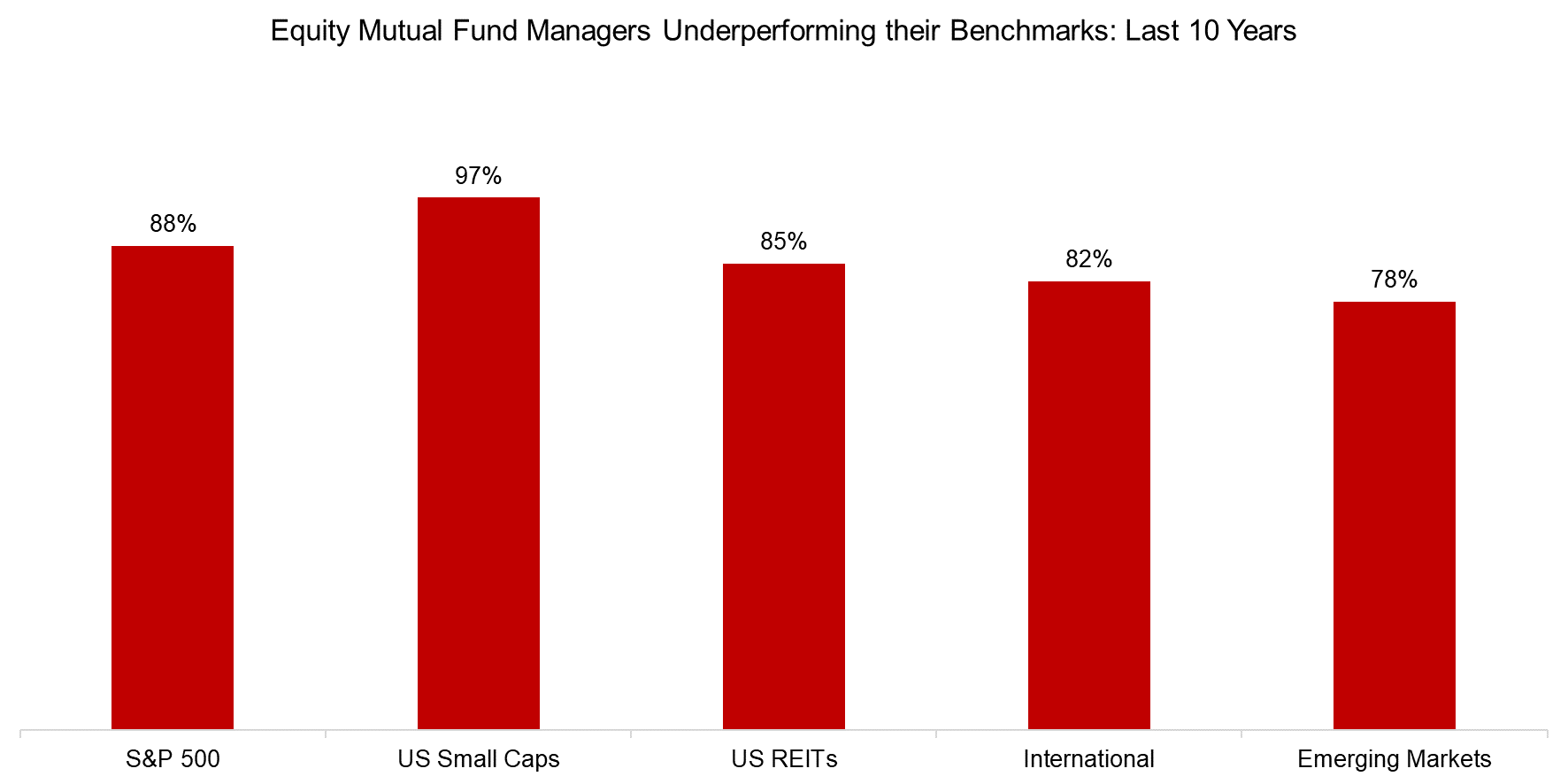

Retail investors are often called naive money in the financial media, however, the track record of professional fund managers is not particularly impressive either. The S&P SPIVA Scorecards show that almost all equity fund managers underperformed their benchmark over a 10-year horizon, which is long enough for a manager to prove his skill. Unfortunately for capital allocators, the lack of skill generating consistent alpha does not only apply to the highly competitive US stock market, but as well to international, market segments, sectors, and even emerging markets.

Source: S&P SPIVA Scorecard 1H 2019, FactorResearch

The evidence is clear that active management in equities does not generate alpha, which is unlikely to change as markets are continuously becoming more efficient. High management fees certainly contribute to the lack of outperformance, but active managers can not reduce fees to those of ETFs.

Simply earning market returns by investing in passive investment products seems to be dissatisfying to most capital allocators. Many have therefore turned to factor investing, which is positioned between active and passive management. The standard approach to creating factors is rules-based, similar to indexing, but the definitions and portfolio construction vary significantly among asset managers, which is comparable to active management. Empirical and academic research show that factors have generated positive excess returns across various asset classes.

In this article, we will explore if factor investing is the free and easy panacea that allows investors to outperform stock markets.

TRUE FACTOR INVESTING

Factor investing is based on the academic literature that shows excess returns from factors like Value and Momentum, which are typically modelled as long-short portfolios. Post the financial crisis in 2008 and 2009, investment managers significantly increased their offering of systematic investment strategies, which includes factor-focused products. For instance, an institutional investor can buy a long-short basket of cheap stocks (according to a few or more metrics like book to price) for a few basis points that effectively replicates the Value factor as seen in papers from Fama and French or other researchers.

More recently such products have become accessible via liquid alternative mutual funds and ETFs, democratizing long-short factor investing for all investors. It is not free like some plain beta products have become, but available at low cost.

However, factors are as cyclical and exhibit extended up and downward trends as well as sharp rallies and dramatic crashes. Given this, investors frequently are advised to combine these into multi-factor portfolios to increase the consistency of returns by harvesting diversification benefits.

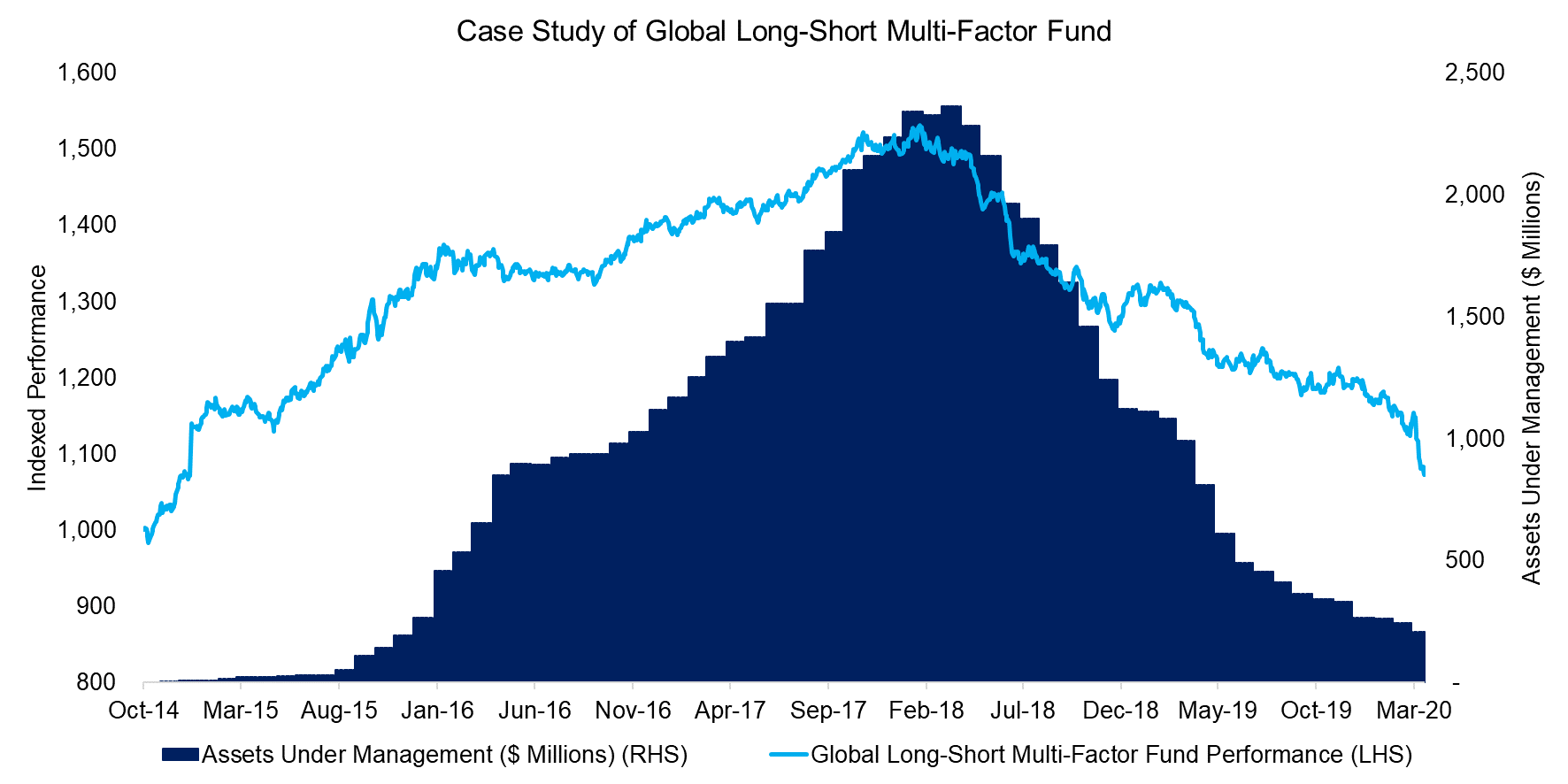

Unfortunately, even cutting-edge, diversified long-short multi-factor portfolios can have significant drawdowns over time. We can use a well-known liquid alternative mutual fund from a large US asset manager as a case study. The fund provides exposure, among others, to the Value, Momentum, and Quality factors via a global long-short portfolio comprised of several hundreds of stocks. The factors are defined in line with academic and industry standards, which makes the fund an excellent proxy for measuring the performance of a classic multi-factor portfolio.

We observe a consistent upward trend in the performance of the fund from 2014 to 2018 and then a steady downward movement thereafter. It is worth highlighting that the product is structured beta-neutral, which means that the performance represents excess returns that are uncorrelated to equity markets, making the strategy attractive for capital allocators from a diversification perspective.

The assets under management increased from slightly above zero to more than $2 billion in 2018, but then decreased by more than 90% to approximately $200 million in 2020. The tale of this fund is essentially the one of all funds. Investors allocate capital to funds that are performing and redeem their capital when returns become negative.

This performance chasing behavior exhibited by investors should be criticized, especially in the case of factor-focused products. Factor investing represents a systematic approach to stock selection and is based on robust research, where the performance of such a portfolio can be simulated (backtesting) from 1926 onward, using data from the Kenneth R. French data library. The current drawdown of 30% is unpleasant and undesirable, but also within the historical range of drawdowns and should be within the expectations of any investor allocating to the fund.

Investing in long-short multi-factor portfolios is theoretically the optimal way to pursue factor investing as long and short positions can contribute returns. Furthermore, these provide attractive diversification benefits for traditional equity-bond portfolios. However, given market neutrality, such portfolios will always behave differently than most other assets in investment portfolios, which requires frequent justification for such an allocation. This characteristic combined with occasional significant drawdowns make long-short factor investing challenging for most investors, despite being cost-efficient and easy to implement via liquid alternative mutual funds and ETFs.

Source: FactorResearch

SMART BETA FACTOR INVESTING

Although long-short factor investing is essentially what investors view when reading academic research, the majority of capital allocated to factor-focused products is invested in smart beta strategies. These represent long-only portfolios with small factor tilts, where most of the returns and risk can simply be explained by exposure to the stock market. Perhaps smart beta strategies represent a more realistic approach for investors to pursue factor investing (read Smart Beta vs Factor Returns).

Theoretically, smart beta products are designed to maximize their factor exposure, however, that requires portfolios to be constructed using different rules to that of a benchmark, e.g. by ranking on a characteristic like past returns versus market capitalization weights. The problem is, the more differentiated the smart beta portfolio from its benchmark, the larger the tracking error. When a combination of large tracking error and negative returns happens, investors struggle to remain invested as they tend to quickly lose faith in underperforming strategies. Although there is no data available for the average holding period for smart beta strategies, equity mutual funds in the US are held barely more than two years.

We create seven smart beta portfolios for the common equity factors namely Value, Size, Momentum, Low Volatility, Quality, Growth, and Dividend Yield, which are used to calculate historical tracking errors. There is little academic support for the Growth factor while Dividend Yield can be viewed as a subset of Value, but both are widely followed investment styles, which warrants their inclusion. The long-only portfolios are constructed by selecting the 30% of the US stocks that rank most highly on the factor definition, are rebalanced monthly, and market capitalization-weighted.

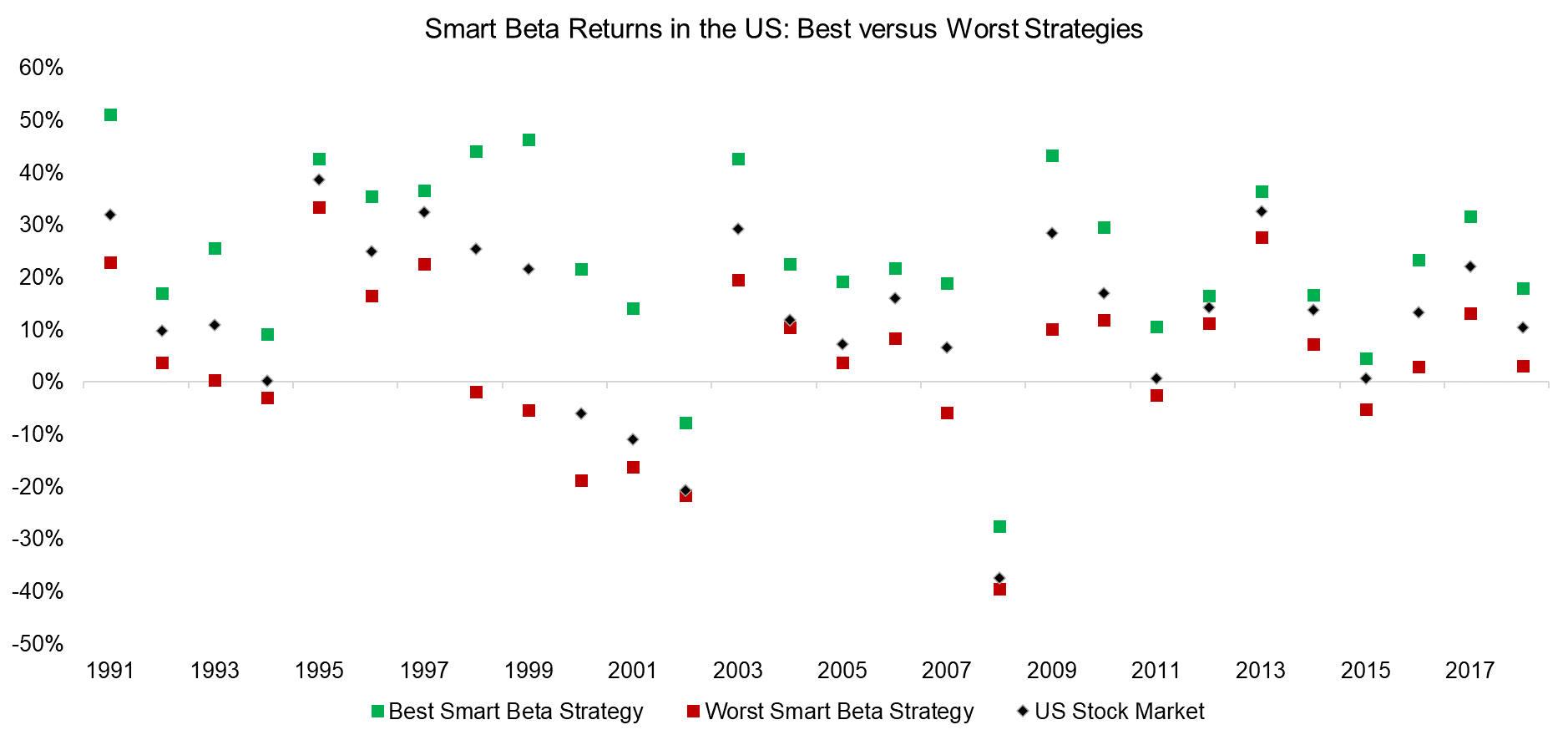

The analysis highlights that the annual returns of the smart beta strategies broadly mirror the US stock market, but we observe significantly different returns from the best and worst performing portfolios. For example, in 1998, the market was up 25%, compared to -2% for small cap stocks, which was the worst-performing smart beta strategy.

Source: FactorResearch

Measuring the tracking error of the worst smart beta strategy in the US from 1991 to 2018 highlights an average annual underperformance of 8.5% compared to the stock market. The smallest negative annual tracking error was -0.8% and the largest -27%, which occurred during the tech bubble in 1999 when investors were chasing exciting technology stocks and selling boring high dividend-yielding stocks.

Factors are cyclical and the performance leaderboard changes continuously, therefore it is unlikely for an investor to always be invested in the worst-performing smart beta strategy. However, investors should expect to occasionally have a substantially negative tracking error.

Given the magnitude of the tracking errors and the tendency of investors to chase performance, it is unlikely that investors will remain committed to single factors after a period of underperformance.

Source: FactorResearch

Naturally investors can combine several smart beta strategies into long-only multi-factor portfolios in order to reduce the drawdowns of single factors. Favorite strategies are combining small and cheap stocks, cheap and winning stocks, or all five factors that are supported by research, which are Value, Size, Momentum, Low Volatility, and Quality (read Multi-Factor Smart Beta ETFs).

All three multi-factor combinations generated positive excess returns between 1990 and 2018, supporting the case for factor investing as a means for outperforming the market, albeit with maximum negative annual tracking errors ranging between -6.6% and -21.2%. The latter would clearly have been too much for almost all investors, while the former may not seem too large considering that we are evaluating an almost 30-year period.

However, most institutional capital allocators define maximum tracking errors of 3% for systematic long-only equity products, which makes even diversified multi-factor smart beta portfolios challenging to hold.

Source: FactorResearch

FURTHER THOUGHTS

The case for factor investing is simple: it allows investors to generate excess returns across asset classes via rules-based investing frameworks. Long-short and long-only products have become available to all investors at relatively low cost, which makes beating the market cheap and easy.

The case against factor investing is equally simple: nothing in investing is truly free. Knowing how the beat the market is quite different to actually doing it. For instance, many have studied the investment style of a well-known investor based in Omaha, Nebraska, yet few, if any, have succeeded at replicating his success.

Allocating to factors when performance is positive and redeeming capital when negative is effectively factor timing, which is likely to be as (un)successful as market timing. Unless investors accept the cyclicality of factor investing and commit to its investment framework even when returns are negative, they are better off not pursuing it.

RELATED RESEARCH

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nicolas Rabener is the CEO & Founder of Finominal, which empowers professional investors with data, technology, and research insights to improve their investment outcomes. Previously he created Jackdaw Capital, an award-winning quantitative hedge fund. Before that Nicolas worked at GIC and Citigroup in London and New York. Nicolas holds a Master of Finance from HHL Leipzig Graduate School of Management, is a CAIA charter holder, and enjoys endurance sports (Ironman & 100km Ultramarathon).

Connect with me on LinkedIn or X.